By Dr. James M. Dahle, Emergency Physician, WCI Founder

By Dr. James M. Dahle, Emergency Physician, WCI Founder

Most of the time, refinancing your student loans is a great move. You enjoy all kinds of great benefits:

- A lower interest rate

- Fewer loans to keep track of

- Better customer service

- Easier to understand terms (government programs can be complicated)

- $300-$1,500 cash back (if you refinance through the WCI Student Loan Refinancing links)

- Free enrollment in our Fire Your Financial Advisor online course (a $799 value) if you refinance $60,000+ through our links

You can see why financially savvy docs refinance their loans early and often. However, there are times when refinancing is not the right move. In today's post, we'll go through those situations. If, despite reading this post, you still aren't sure whether you should refinance, we recommend you hire Andrew Paulson at StudentLoanAdvice.com to help you run the numbers and make a decision.

Refinancing Private Loans

One situation that isn't complicated is when you have private loans. There is no risk in refinancing these. Any time you can get a lower interest rate, you should refinance these. Heck, even if you get the same interest rate, you should refinance through our links and get back a few hundred bucks (and the Fire Your Financial Advisor course). Private loans aren't eligible for federal forgiveness or income-driven repayment programs, so there is no harm in refinancing them. If you are worried about cash flow during residency or fellowship, you'll be pleased to know that several companies offer you the ability to make payments of just $100 a month until you finish training.

Public Service Loan Forgiveness

The Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program is one of the best possible ways to manage federal loans. If you are eligible for this program by virtue of your employment situation, you should almost surely take advantage. PSLF offers tax-free forgiveness of any remaining direct federal loans after 10 years of payments have been made.

Public Service Loan Forgiveness Requirements:

- Only direct federal loans are eligible

- Must be employed full-time (30+ hours per week) by a nonprofit (501(c)(3)) or governmental employer

- Must make 120 on-time monthly payments in an eligible program (usually an Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) such as Income-Based Repayment (IBR), Pay As You Earn (PAYE), or Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE))

- Must correctly fill out the annual employer certification forms and application

A doctor who does a three-year residency and a three-year fellowship and then works as faculty in the program for four years may have more debt forgiven than was actually borrowed to pay for medical school, and it's all tax-free. Needless to say, doing anything that jeopardizes this when you would otherwise qualify would be a terrible mistake. One of those things is refinancing your student loans. When you refinance (not consolidate) your direct federal student loans, they are no longer direct federal student loans. Instead, they become private loans, and thus, they are no longer eligible for PSLF. So if you are:

- Definitely going for PSLF (i.e. planning on working full-time for a 501(c)(3)),

- In the military,

- Think you might work for a 501(c)(3), or

- Could even possibly work for a 501(c)(3) in the next few years,

then don't refinance your federal student loans. (You can still refinance your private ones early and often, of course.)

Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) Forgiveness

While PSLF is a no-brainer, the other forgiveness programs out there for federal student loans require a lot more thought and number-crunching. IBR, PAYE, and REPAYE all offer a forgiveness program. While there are slight differences, there are many similarities:

- Do not have to work for a 501(c)(3) (or even work at all)

- Do not have to work full-time

- Require 20-25 years of payments (20 for PAYE and 25 for IBR and REPAYE for grad/professional school loans)

- Amount forgiven is fully taxable as ordinary income in the year it is received

I've never been a big fan of IDR forgiveness for the 12 reasons outlined here. The two most significant of those reasons are the tax bomb and the long period of indebtedness.

The Tax Bomb

Imagine a doctor who gets $800,000 forgiven this year. Let's say that doctor is single and making $300,000 this year. That $800,000 is added on to that $300,000 income. Let's say the doctor lives in a high-income tax state, too. What is the tax bill for this forgiveness? Well, this doc has already filled the 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, and part of the 35% bracket with current earnings. In 2021, the entire amount forgiven is taxed at 35% ($223,600 * 35% = $78,260) or 37% ($576,400 * 37% = $213,268) for a total of $291,528. Add on about 12% ($96,000) for California state income tax and we're up to $387,258, almost half of the amount forgiven. That is probably more money than the original debt (which grew over 20-25 years).

Now the size of the tax bomb is going to be different for everyone that gets IDR forgiveness, but it certainly makes the program dramatically less attractive than PSLF. So much so that when I see somebody going for it, I can't help but ask, “Really? You're really not willing to go work full-time at a 501(c)(3) for 4-7 more years? You REALLY can't find a job anywhere in the country that qualifies for PSLF?” Too many people who go down this path simply trade a debt to the Department of Education for one to the Department of the Treasury (IRS). I can tell you which department of the government I'd rather owe!

The Long Period of Indebtedness

My biggest problem with IDR Forgiveness programs is that they require you to be in debt for 20-25 years. Even if you do a three-year residency and a three-year fellowship, you will still have student loans in your life for 14-19 years after you finish training. I'm 15 years out of training, and I am financially independent. I have not thought about my student loan debt for 11 years. I have zero regrets about getting that out of my financial life within four years of finishing training so I could focus on other financial priorities. I cannot imagine having student loans at an age when many other docs could retire. It is super depressing for me to even think about. So, it is hard for me to recommend that path to anyone but the most desperate, no matter how the numbers shake out.

Who Does IDR Forgiveness Work Out Well For?

It would be a lie, however, to say the numbers don't shake out well for some people. Here are the factors that make it more likely to work out well for you:

- Not working for any reason

- Non-working spouse

- Low-earning spouse

- Working part-time for any reason

- Large family size

- High household debt-to-income ratio (2.5X+)

- High debt levels ($300K+)

- Ability and willingness to invest aggressively and stick to a long-term plan

For most of these (numbers 1-6), the reason it works out better is that it results in lower IDR payments, which leads to more forgiveness. In addition, factors 1-5 also reduce the tax rate applied to the tax bomb. High debt levels make IDR forgiveness more attractive because you are likely to have a high debt-to-income ratio and simply because there is more money at stake, making you more willing to go through the hassles inherent in dealing with a government program for over two decades. The discipline and investing ability matter because there is no other way to save up for the tax bomb than to start early and to invest regularly toward that goal. You're simply not going to be able to cash flow a six-figure tax bill.

The Comparison

If we take two identical families and compare a strategy of refinancing and paying back their student loans quickly with massive sacrifice (i.e. live like a resident for 2-5 years) to an IDR forgiveness strategy, you have to compare the extra principal paid back by the non-forgiven doc to the additional interest paid by the forgiven doc plus the amount put toward the tax bomb. To make the comparison, one must make some assumptions. If you don't like my assumptions, make your own and run the numbers yourself. I'm going to assume 6% after-tax returns on investments and that tax brackets remain the same but increase by 3% a year with inflation. I'm also going to assume that income climbs 3% a year with inflation. I also make the simplifying assumption that the doctor did what many doctors (incorrectly) do and left the student loans in forbearance during training.

Case Study: A Single Doctor in California

This doctor makes $200,000 and finished residency with $400,000 in direct federal student loans at 6% and enrolled in PAYE.

A PAYE calculator shows us the following:

Total amount paid of that original $400,000 would be $491,934, leaving almost the original debt to be forgiven, $388,086. The tax bill on that in California is going to be in the range of 40-45%. Let's call it 40% just to make it not look so bad.

$388,066 * 40% = $155,226

So, in addition to paying $491,934 to the lender, the doc also has to pay $155,226 to the taxman! That's a total of $647,160 on an original debt of $400,000. Does that sound like loan forgiveness or loan “cancellation” to you? Me neither.

Now imagine this doctor had buckled down and paid off this debt over five years by living like a resident. How much would have been paid? Well, let's assume it was refinanced to 3%. The doc would pay $87,000 a year for five years for a total of $437,000. Which would you rather pay: $437,000 or $647,000? Easy decision, right?

However, that's not quite the question. The question is would you rather pay $437,000 over five years or $647,000 over 20 years, and that's a much different question. There's a time value of money calculation in there somewhere. For example, consider the debt bomb. You don't really have to pay $155,000 to the taxman if you invest toward that goal for 20 years. At 6%, you only have to invest

=PMT(6%,20,0,-155226) = $4,220 per year or $84,400

That lessens the pain, right? Let's also consider an alternative use for that money you sent to the lender while living like a resident. Let's say you invested it instead. If the doc going for forgiveness pays $1,516 * 12 = $18,192 to the lender and $4,220 to the tax bomb fund in year one, that's $87,000 – $18,192 – $4,220 = $64,588 that can be invested. The amounts invested in years 2-5 are similar. Then, of course, you have to make the same calculation for the doc who lived like a resident for the next 15 years with the money saved by not making student loan payments for those 15 years. Then you have to compare it all to each other. Ugh. And people are supposed to do this themselves to make a decision? Give me a break.

Let's make some more simplifying assumptions. Let's say the doc going for forgiveness puts away $62,000 a year for five years, then lets it ride for 15 more at 6%, and let's say the doc who lived like a resident saved $26,000 a year for 15 years and earned 6% on it. How does it work out?

For the forgiveness doc, it adds up to =FV(6%,15,0,-FV(6%,5,-62000)) = $839,000.

For the live like a resident doc, it adds up to =FV(6%,15,-26000) = $605,000.

That's a $234,000 difference, which barely makes up for the extra $210,000 in extra debt payments.

So mathematically, and assuming all these assumptions are accurate, going for IDR would be better for this doc, but not by much. Enrolling in PAYE in residency would help, as would earning a higher investment return. But I think most people who run the numbers and get this result would probably just choose to refinance and pay off the debt. But what if the doc had $600,000 in debt and a family of four? Now the IDR forgiveness scenario looks way better. Just look at the calculator results:

How much would this doc have to pay a year in order to pay off $600,000 in student loans in five years? Oh, just $131,000 a year. No problem in California on a gross income of $200,000. Even with a need to invest $12,000 a year or so at 6% to meet that huge tax bomb, this is still a more attractive route than refinancing and paying off.

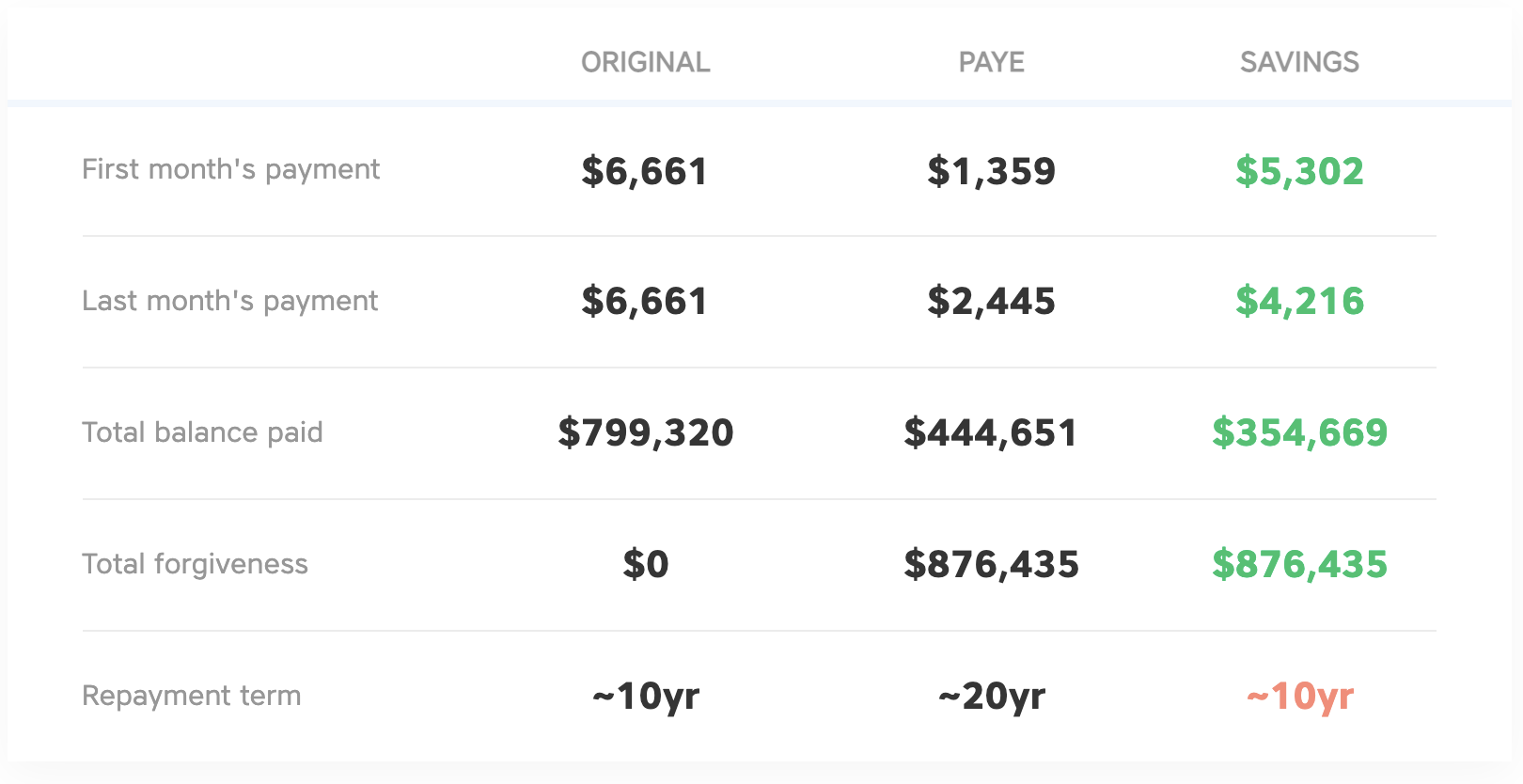

Some readers might be wondering what happens to IDR forgiveness if you're not in a desperate student loan situation. An example might help. Consider a doctor with $200,000 in student loans who makes $300,000 and enrolls in PAYE. Monthly payments are about $2,200, and you end up paying off the loan in just over 10 years. You would have been better off refinancing, even if you had just refinanced into a 10-year loan.

There are no hard and fast rules, of course, and you have to look at your own personal situation. But in my opinion, here is a good rule of thumb for those not going for PSLF:

- If your student loan-to-income ratio is < 1.5, go ahead and refinance and pay those loans off ASAP.

- If your student loan-to-income ratio is > 2.5, IDR forgiveness is likely a good option

- If your student loan-to-income ratio is between 1.5 and 2.5, you really need to run the numbers. For a flat fee, you can get help doing that from StudentLoanAdvice.com, a White Coat Investor company.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of docs in that 1.5-2.5X range, and that's one reason why we started a student loan advice company. It's just too complicated for most people to figure out on their own.

What do you think? Are you going for IDR Forgiveness? Why or why not? Comment below!

[Editor's Note: This updated post was originally published in 2018. Many of the comments below pertain to a similar article written by a different author in 2018.]

Is refinancing right for your situation? Refinance at today's low rates and get cashback!

† Bonus includes cash rebates and value of free course. Borrowers who refinance more than $60,000 in student loans using the WCI links will be enrolled in The White Coat Investor’s flagship course, Fire Your Financial Advisor for free ($799 value). Borrowers will still receive the amazing cash rebates that WCI has negotiated with each lender. Offer valid for loan applications submitted from May 1, 2021 through January 31, 2022. Free course must be claimed within 90 days of loan disbursement. To claim free course enrollment, visit https://www.whitecoatinvestor.com/RefiBonus.

The post Which Physicians Should Not Refinance Their Student Loans? appeared first on The White Coat Investor - Investing & Personal Finance for Doctors.