If art is meant to disturb and provoke, the national coat of arms on the gate of a school in my neighbourhood is a masterpiece. A feeling of an essential, visceral wrongness came across me when I walked past it last Independence Day, a feeling on a level somewhere deep, beneath logic and reason.

It was the expression on the kob’s face. It looked as if it was asking the crested crane standing opposite if she knew what on earth they were doing there.

The crane herself seemed to gesture, “Simanyi. Nze I was told to come and hold the shield so I came and now I’m holding the shield.”

The painter had painted what looked like a shrug on a bird with no shoulders.

We educated patriots were taught and probably still remember the meaning and significance of the shield, its animal consorts and the stuff that surrounds it– the rivers, mountains, the colours — the coat of arms is a symbol made of symbols of Uganda.

And that is what disturbed me that day: the fact is that a coat of arms, especially one with a shield in between two animals, is a British thing.

The kob and the crane are Ugandan things but a coat of arms is not. It’s a European thing. This one, a British thing.

Uganda was created in Britain’s image and, since independence, has been trying to recreate herself in the same guise.

It was Uganda’s Independence Day 2020.

I only think of Independence on Independence Day. We have seen so many Independence days come and go, we have heard the word so many times, and then heard so many other words swooshing in after and before it in the 281 days prior and in the 83 subsequent to the ninth: words like balance of payments, trade deficit, non-aligned movement, neo-colonial, puppet, debt, white savior, reparations, relief, interests… so much has been said and seen over 58 years that we have run out of credulity.

There is the picture that sparks by reflex through the mind when Independence is mentioned– there we were, jolly, happy black men and women living our tropical, hassle-free lives under the equatorial sun, when a black cloud descended (Or, rather, a white cloud) and broke into a storm that washed away our liberty. We were thrust into the shackles of white imperial oppression, there to languish until the irrepressible Afrikan spirit of valour Wakanda’d up and we finally got rid of them Babylon colonisers.

But if I were to keep following that story, I would expect that we would then return to the old ways. The Muzungu is gone, so let’s return to our herds and huts and shambas and our happy, sunlit lives.

But of course we didn’t. We couldn’t because it was never real. It’s oversimplified to the point that it is untrue. You can’t mend what was never actually there to be broken in the first place.

What actually happened was that Britain arrived, found land, resources, people, climate and opportunity, took them and created Uganda out of it.

They did not come and colonise Uganda because there was no Uganda before. They made Uganda.

And so when they left, Uganda could not go back to what it was before, because it was not even there before.

It seemed the natural thing to do, then, to just proceed as per. With no British governor present, to then go on and just colonise ourselves.

When the White Man departed he did not leave entirely. Aspects of his culture and manners remained and the new nation has since shown itself to be, in many ways, a dustier version of the abandoned British toy.

Colonies and “protectorates” were designed to be looted and oppressed by their dominator governments and our independent governments have done their best to continue that work in those roles the governors left vacant. But, as you can see from the kob’s face, questions remain unsettled.

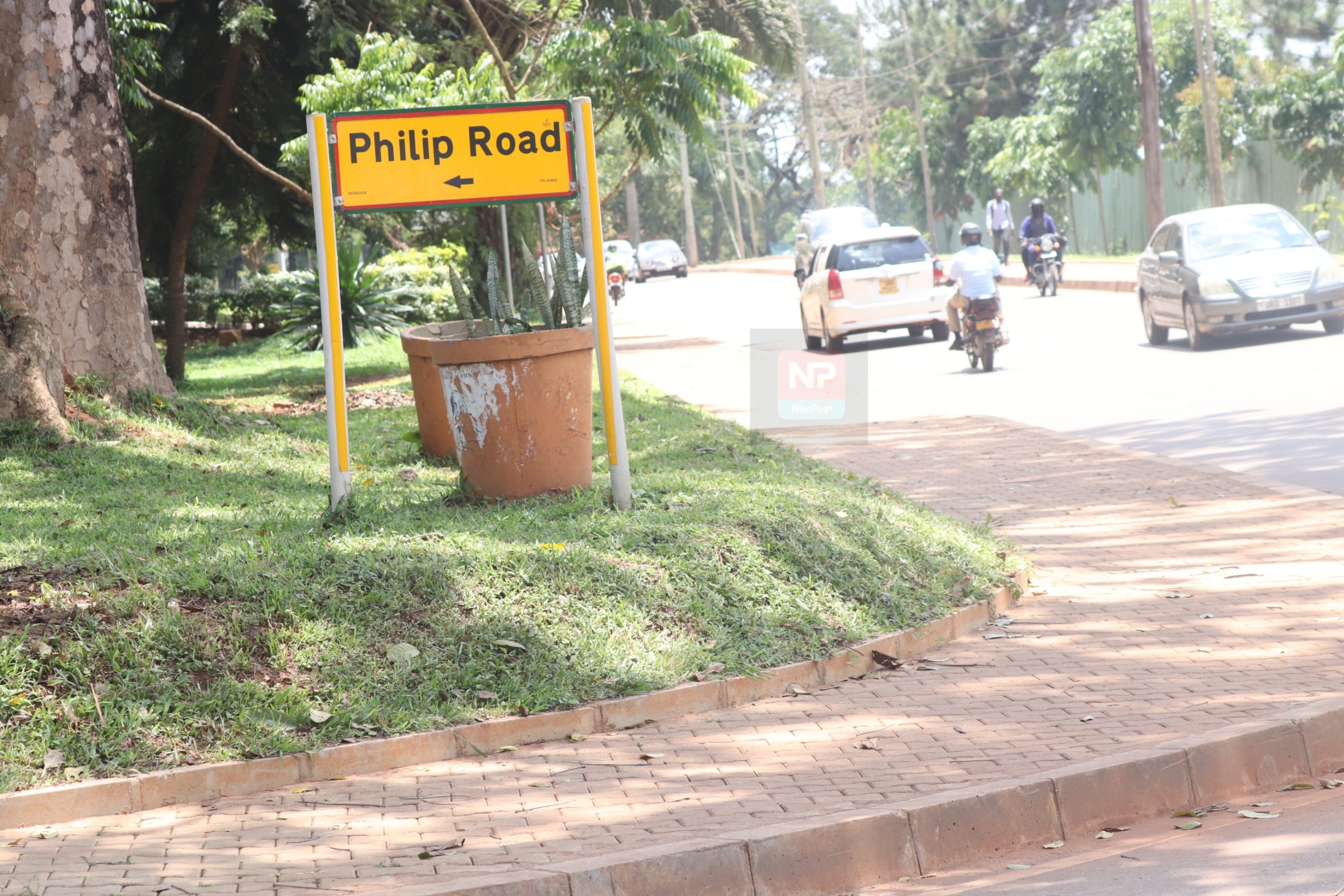

It’s not just the series of kleptocracies and incompetentocracies and croniocracies that have plagued our five decades, but also this: even all these years after Muzungu left, we still have his names on our streets.

The least we could do is change Prince Charles Drive to something more befitting a free republic.

Don’t get this misread, patriots and compatriots; the Ugandan people have overcome much, achieved a lot, created, built and, yes, developed a lot since 1962, and there are many reasons to celebrate our independence day.

We did that on Friday the ninth. We celebrated. Now we can go back to doing what citizens of a free nation are duty-bound to do, which is complain about what hasn’t yet been done.

In this case, look at these street names. It’s not befitting, surely.

One of the more underrated acts of development Uganda has achieved is boda boda transport. Development is not Anglicisation; civilization is not Britishisation. It is applying your means to your problems to solve them. The boda boda epitomizes this. Our problem was a tiny village designed to house smug imperialists that had burgeoned into a sprawling city full of plebians with places to go and things to do, but bereft of adequate road channels to let them drive to work without choking traffic jams. Boda bodas, for all their shortcomings, addressed that.

But they still have to cut through Prince Charles Drive to get me to work.

Like the ill-mannered uninvited guests they were, the colonialists left some turds unflushed when they departed in 1962, and Idi Amin was one of them. Mr Amin renamed what were Lake Edward and Lake Albert, though he named them after himself and Mobutu Seseseko, so the final effect was like replacing a slap with a punch.

In 1972, Amin declared that Prince Charles Drive would henceforth be known as 25th January Avenue, after the date he took over Uganda. Naturally, once we got independence from Amin, we ditched that name.

He renamed quite a few streets and roads before he left and we kept the names he chose that didn’t suck. Like Nkrumah, Lumumba and Nasser roads, for example, to honour Africans of honour. Because naming streets should be an honor.

Ghana’s President Kwame Nkrumah addresses parliament in 1960. In 1957, Ghana became the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to declare independence (AFP Photo/)

Some names, however, weren’t changed, even though some of the colonialists are still spinning in their graves wishing we would.

Take Speke Road for example.

Named after John Speke, the explorer who thought he discovered the source of the Nile river, is right in the center of Kampala. There’s no honour in having that particular road named after you. It’s a dishonourable stretch of tarmac if any ever was, especially so for an explorer who named our lake after the monarch of Victorian England, which is still a byword for sexual repression.

Speke Road is notorious as Kampala’s main hoe stroll. The red light district. Where the hookers be at. If it weren’t for the ongoing Covid curfew, your morals or your financial state (pick a reason) you could go there tonight and chose any one of dozens of sex workers standing on the kerb waiting for a John (that’s fittingly the industry term for a hooker’s client). The John can buy sex with them if he has enough money. Money which talks. You can be a John if your money Speaks.

Then again, perhaps they should leave Speak Road un-renamed since it’s such a fitting metaphor of colonialism. The colonised people kowtowing to their imperial masters are like the sex worker faking pleasure and praising the client’s performance, moaning, “I’m yours! You are the greatest! You’re my king!”

We can’t forget that these were not just racist people, but deeply invested ones. Career racists. These were men whose disdain for us was such that they were not just content to just talk the talk. Lugard Road is now a quick shortcut if you want to avoid Kampala Road traffic. Frederick Lugard wasn’t content to just say of the black African that, “His mind is far nearer to the animal world than that of the European.” This from a barbarian who travelled halfway across the world to order death and plunder. Geoffrey Archer, who gives his name to Archer Street, magnanimously permitted the Africans under his watch the use of their brains, but only let us study simple clerical work. You were trained to take orders and do what white bosses told you to. Lugard and Archer had minds far nearer to the brute or even the scavenger world, evidently.

Operation Legacy was a last-ditch purge where they burned and destroyed papers and records that may have, you never know, included evidence of the savage acts committed by a racist state enforcing its oppression, but it didn’t destroy all traces of Governer Henry Colville’s atrocities, and the diaries of former soldiers allegedly tell of quite a bit of rape, murder and torture at his command.

Colville Street still stands in Kampala, though, a busy rise up to Christ The King Church.

Maybe we should just look back to our past to name our future. How were things named before Uganda?

Uganda has several diverse naming customs, but major places of importance tend to be named after morally neutral things, not people. Kabale town was, according to the legend, named after a piece of stone that had some iron hidden within it, making it so heavy that no one could lift it. People would come from far and wide to try, then fail, to lift it, and the place came to be known as “small stone”. Mbarara is said to be named after a type of grass from the area and one story says that Gulu is from the sound of heavy rain that would fall in the valleys– thunder and pounding rain going, “Gulugulugulu!”

Maybe a more Ugandan way of naming our Uganda would make it more… Ugandan. Maybe the secret to carving ourselves into a successful nation is not in continuing with colonial Uganda, or repeating colonial Uganda, but is in something some time before that, before Uganda.

Our national anthem is as apt as a beer commercial. It is whimsically vague, insincere sentiment and one can easily be a fine Ugandan without it as one would without kobs brandishing shields.

I seem to remember, in my ancestral memory, a thing called drums.

Drums have force and power, and if a people need sound to assert who they are, why should we cast aside our wood and hide thunder-makers for something as twee as this national anthem?

Or how about changes in government and leadership? We have obviously abused the title Honourable to shreds so flimsy that any brigand, bully and buffoon can claim it just by deceiving and tricking enough people.

How about we replace this pastiche of a Parliament we badly copied from the UK with perhaps some form of congregation of people’s representatives who are held accountable to the people they work for and are required by custom to treat us with respect and not just the other way round?

It might work, it might not, but that’s History for you.

We have spent fifty eight years defining ourselves as a nation and defining a nation as a colony that doesn’t have bazungu any more.

No wonder the poor kob had no idea what it was doing by that shield.

The post UGANDA AT 59: After the British left, we colonised ourselves appeared first on Nile Post.