Excerpt: The Fortune Men by Nadifa Mohamed

Kow

One

Tiger Bay, February 1952

‘The King is dead. Long live the Queen.’ The announcer’s voice crackles from the wireless and winds around the rapt patrons of Berlin’s Milk Bar as sinuously as the fog curls around the mournful street lamps, their wan glow barely illuminating the cobblestones.

The noise settles as milkshakes and colas clink against Irish coffees, and chairs scrape against the blackand white tiled floor.

Berlin hammers a spoon against the bar and calls out with his lion tamer’s bark, ‘Raise your glasses, ladies and gentlemen, and send off our old King to Davy Jones’s Locker.’

‘He’ll meet many of our men down there,’ replies Old Ismail, ‘he better write his apologies on the way down.’

‘I b-b--bet he wr-wr-wr-ote them on his d-d-d-eathbed,’ a punter cackles.

Through the rock ’n’ roll and spitting espresso machine Berlin hears someone calling his name. ‘Maxa tiri?’ he asks as Mahmood Mattan pushes through the crowd at the bar.

‘I said, get me another coffee.’

Berlin catches his Trinidadian wife’s waist and steers her towards Mahmood. ‘Lou, sort this troublemaker another coffee.’

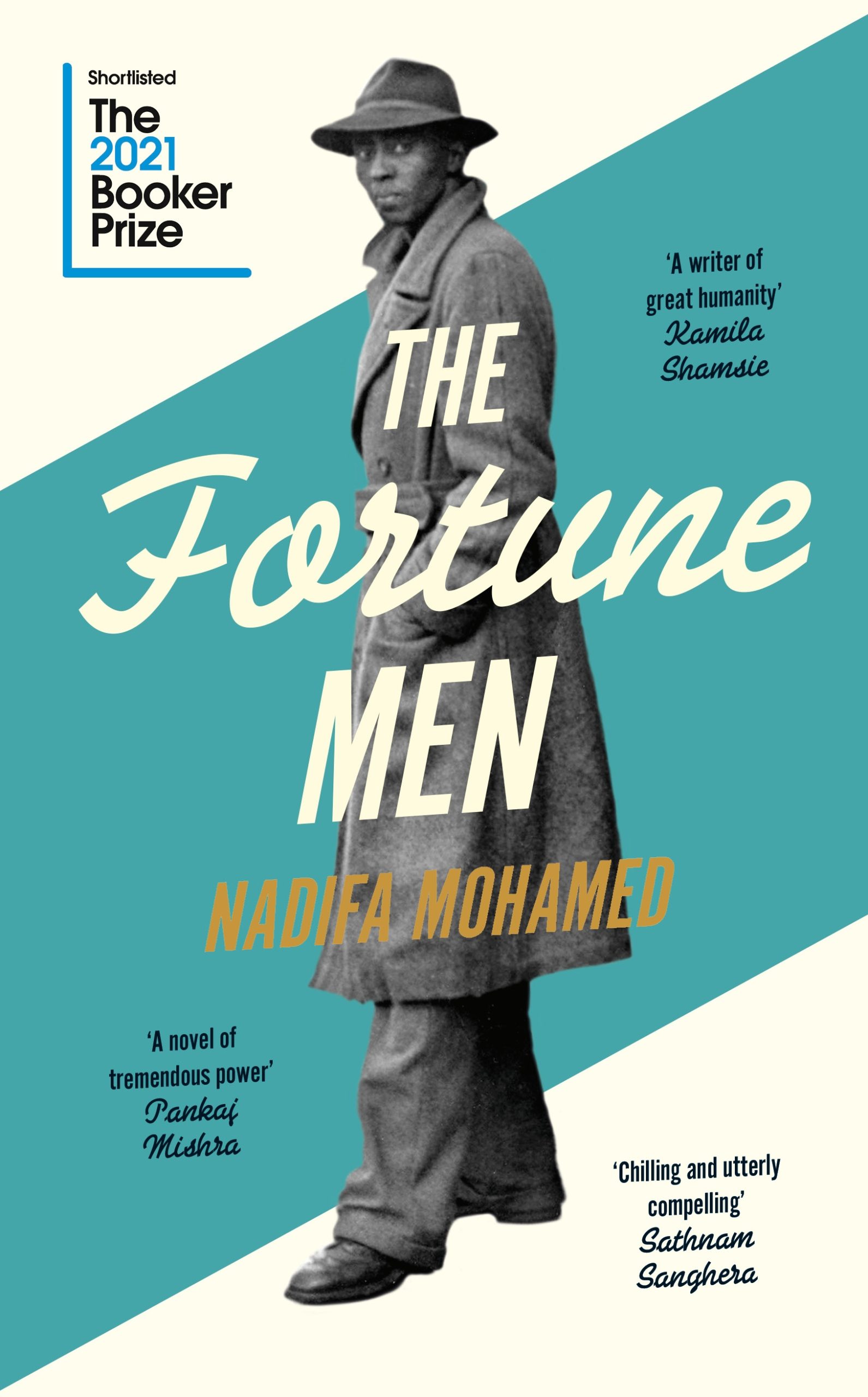

Ranged along the bar are many of Tiger Bay’s Somali sailors; they look somewhere between gangsters and dandies in their cravats, pocket chains and trilby hats. Only Mahmood wears a homburg pulled down low over his gaunt face and sad eyes. He is a quiet man, always appearing and disappearing silently, at the fringes of the sailors or the gamblers or the thieves. Men pull their pos sessions closer when he is around and keep their eyes on his long, elegant fingers, but Tahir Gass ‒ who was only recently released from Whitchurch asylum ‒ leans close to him, looking for friendship that Mahmood won’t give. Tahir is on a road no one can or will walk down with him, his limbs spasming from invisible electric shocks, his face a cinema screen of wild expressions.

‘Independence any day now.’ Ismail gulps from his mug and smiles. ‘India is gone, what can they say to the rest?’

Berlin makes his eyes bold. ‘They say we got you by the balls, darkie! We own your land, your trains, your rivers, your schools, the coffee grains at the bottom of your cup. You see what they do to the Mau Mau and all the Kikuyu in Kenya? Lock them up, man and child.’

Mahmood takes his espresso from Lou and smirks at the exchange; he cares nothing for politics. While trying to straighten his cufflinks a drop of coffee runs over the rim and falls on to his brightly polished shoes. Grabbing a handkerchief from his trouser pocket, he wipes it off and buffs the stain away. The brogues are new and as black and sharp as Newfoundland coal, better shoes than any other fella here has on his feet. Three £1 notes burn away in his pocket, ready for a poker game; saved through missed lunches and nights spent without the fire, mummified in his blankets. Leaning over the bar, he nudges Ismail. ‘Billa Khan coming tonight?’

‘Me come from the jungle? I wish I come from the jungle! I said to him, look around you, this is the jungle, you got bushes and trees everywhere, in my country nothing grows.’ Ismail finishes his joke and then turns to Mahmood. ‘How would I know? Ask one of your crooks.’

Kissing his teeth, Mahmood throws the espresso down his throat and grabs his fawn mackintosh before stalking through the crowd and out of the door.

The cold air hits his face like a spade, and despite urgently forcing the jacket around his body the bitter February night takes hold of him and makes his teeth chatter. A grey smudge hovers over everything he sees, the result of a hot chink of coal flying from a furnace and into his right eye. A pain so pure that it had hoisted him up and backwards on to the cooling clinkers behind his feet. The clatter of shovels and devil’s picks as the other stokers came to his aid, their hands tearing his fingers from his face. His tears had distorted their familiar faces, their eyes the only bright spots in the gloomy engine room, the emergency alarm clattering as the chief engineer’s boots marched down the steel staircase. After wards, two weeks in a hospital in Hamburg with a fat bandage wrapped around his head.

That smudge and a bad back are the only physical remnants of his sea life. He hasn’t boarded a ship for near to three years; just foundry work and poky little boilers in prisons and hospitals. The sea still calls, though, just as loudly as the gulls surfing the sky above him, but there is Laura and the boys to anchor him here. Boys who look Somali despite their mother’s Welsh blood, who cling to his legs calling ‘Daddy, Daddy, Daddy’ and pull his head down, mussing up his pomaded hair for forceful kisses that leave his cheeks smelling of sherbet and milk.

The streets are quiet but the news of the King’s death drifts from many of the low slung windblown terraces he passes. Each wireless set relaying the broadcast discordantly, either a second ahead or delayed. Passing the shops on Bute Street, he finds a few lights still on: at Zussen’s pawnbroker’s where many of his clothes are on hock, at the Cypriot barbershop where he has his hair trimmed and at Volacki’s where he used to buy seafaring kits but now just bags the occasional dress for Laura. The tall grand windows of Cory’s Rest are steamed up, with figures laughing and dancing behind the leaded glass. He peeks his head through the door to check if some of his regulars are there, but the West Indian faces around the snooker table are unfamiliar. He had once belonged to this army of workers pulled in from all over the world, dredged in to replace the thousands of mariners lost in the war: dockers, tallymen, kickers, stevedores, winch men, hatch men, samplers, grain porters, timber porters, tackle men, yard masters, teamers, dock watchmen, needle men, ferrymen, shunters, pilots, tugboatmen, foyboatmen, freshwater men, blacksmiths, jetty clerks, warehousemen, measurers, weighers, dredgermen, lumpers, launch men, lightermen, crane drivers, coal trimmers, and his own battalion, the stokers.

Mahmood turns away from the wreathed and porticoed splendour of Cory’s Rest towards the docks, from where a red mist tints the raw, uncooked sky. He enjoys watching the nightly, industrial spectacle: the dirty sea water appearing to catch fire as vats of rippled, white-hot furnace slag from the East Moors Steelworks tip into the lapping evening tide. The railway on the foreshore bank clanking and screeching as carts shoot back and forth between the billowing steelwork chimneys and the angry, steaming sea. It’s an eerie and bewitching sight that catches his breath every time; he half expects an island or volcano to spit out from that bubbling, hissing stretch of petrol-streaked water, but it always cools and returns to its morose, dark uniformity by morning.

The docks and Butetown cover only a square mile but for him and his neigbours it’s a metropolis. Raised up from marshland the century before, a Scottish aristocrat built the docks and named the streets after his relatives. Mahmood had heard a rumour that the world’s first million-pound cheque was signed at the Coal Exchange. Even now, in the morning, a different calibre of men come bowler-hatted to work at the Mercantile Marine Office or the Custom House. At both the Marine Office and Seaman’s Union you know which door to use if you don’t want trouble, and this goes for the labouring white men as well as black. Beyond the financial district, the neighbourhood is for everyone, all of them hemmed in and pushed close by the railway tracks and canals cutting them off from the rest of Cardiff. A maze of short bridges, canal locks and tramlines confuse the new visitor; just before his time, Somali sailors would wear the address of their lodging house on a board around their neck so that passersby could help navigate them. The canals are a playground to young children and once, when two went missing, Mahmood had spent a blue, insomniac night searching the muddy water for any sight of them. They had been found in the morning ‒ one white, one black, both drowned. But his boys are still too young to go wandering, alhamdulillah. One day, when they are older, he will show them around this port town with its Norwegian Church and kosher abattoir, its cranes, booms and smoking chimneys, its timber ponds, creosote works and cattle yards, its three broad thoroughfares – Bute Street, James Street, Stuart Street – crisscrossed with ever-narrowing terraces. The flags and funnels of the world’s shipping fleets crowding the pierheads and sprawling across the dock basins.

Mahmood silently plans the future but now, defeated by the icy chill sneaking itself through the gaps between his coat buttons, he decides against another night of poker and heads home to Adamsdown, where the real fire in his life burns.

Violet collapses heavily into the wooden chair and waits for Diana to set the table. ‘Where’s Gracie?’

‘Just finishing up her extra schoolwork, she’ll be down in a minute.’

‘I think she’s working too hard, Di, her little face looks haggard.’

‘Don’t be ridiculous. She is barely putting pen to paper, spent most of the evening going through my high heels and jazz records. I went up to chivvy her along and her face was smeared in Max Factor Sunset Shine. She thinks she’s set for Hollywood, that one.’

‘The cleaner said that when she was changing her bed sheets she found a photo of Ben in his flight suit under her pillow.’

‘I know.’ Her smile stiffens and she turns her back to Violet.

Violet squeezes Diana’s forearm. ‘Strength, Sister. Koyekh.’

‘Come on down, Grace, we’re waiting for you!’ Diana shouts up the stairs, ripping her apron off and folding it over the back of her chair. The pounds she put on over the Christmas holiday still show on her muscular body and her green wiggle dress strains across the back. Her black hair folds into loose waves over her shoulders; she needs a haircut but Violet likes it like this, it gives her sister a Mediterranean look.

‘You are a perpetual motion machine.’

‘Not by choice, I tell you. Maggie got Daniel to drop off the chicken as I had so many customers earlier. Every last one of them wanted to put his money on a horse with some kind of association with the King: “His Majesty”, “Balmoral”, “Buckingham Palace”. I don’t know if it’s their way of paying their respects or just superstition but I’ve never seen anything like it.’

‘I saw one of them cash his advance note of pay with me and then go through to you. A fool and his money…’

‘Oh, that’s poor Tahir, he’s not right in the head. One of the sailors told me that he was “misused”, as they say, by Italian soldiers in Africa. He tells me he’s the King of Somalia and killed thousands of men in the war.’

‘Which horse did he put money on?’

‘The Empress of India,’ Diana says, splitting her red lipped mouth with a loud laugh. ‘I suppose he thinks that’s his wife.’

‘Goodness gracious. Let me go wash my hands quickly.’ Violet smiles, looking over the spread on the table: roast chicken, pickled gherkins, boiled potatoes, carrots with red onion and beetroot, and a pile of poppyseed bialys. She returns from the sink and slips her stockinged feet out of her black orthopaedic tie-ups, stretching her serpentine spine, scoliosis having made a puzzle out of her ribcage and shoulder blades. She is paler than both Diana and Maggie, her face their father’s down to the deep furrows on either side of her mouth, a nunlike purity to both her dress and to her pink cheeked face. Her hair is still dark but the promise of a white widow’s peak suggests itself above her sparse eye brows. She gives the impression of someone who has always looked older than her real age and is now at the point of inhabiting a body tailored to her: the modest Cardiff shopkeeper.

‘Turn on the wireless, Di, I want to hear the rest of the news. Imagine Princess Elizabeth ‒ sorry, Queen Elizabeth ‒ getting the liner back, knowing she has to give up her calm little life with her husband and babies to take the throne.’

‘No one is making her. She can stay in Kenya and declare the end of the monarchy for all I care.’

‘You have no sense of duty. How could she do that when a whole country, a whole empire, is waiting for her?’

‘You would say that, you daddy’s girl. You make me laugh, Violet, Da leaves you this shop and you take it as seriously as if he had left you the entire world. I can imagine your face in the papers today, talking about your solemn pledge to rule 203 Bute Street to the best of your power, with the help of Almighty God.’

‘This shop is my life, and if I had just sold it in ’48 what good would that have done? A widow, a spinster and a little girl, jumping from home to home and job to job.’

‘We could have gone to London or New York.’

‘To start again? No, Diana, you’re still young enough to get married and have more children. I couldn’t.’

‘Of course you could. Maybe not the kids, but you could certainly get married.’

‘Should I go rooting through the rascals and charlatans who would only want me for my business?’

‘Fine, fine. Your choice.’ Diana raises her hands in surrender and then hollers at the top of her voice, ‘Grace! Get down here this instant.’

‘Coming!’

‘Just come! Aunty Violet is tired, and the food is get ting cold and slimy.

Thuds pound down the winding staircase and then there she is ‒ the centre of both of their worlds ‒ four feet five of undiluted hope and promise.

She kisses Diana and Violet on their cheeks and then wriggles into her chair. Grace’s soft round face is changing shape, Ben’s square jaw pushing itself out and her nose taking on a fine Volacki curve. Ten summers, ten winters without him, thinks Diana, casting a glance over her daughter’s freckled face.

‘Did you get any of your exam practice done, petal?’ Violet asks her, cutting into the chicken and putting three slices on to Grace’s plate.

Grace takes a big bite from a bialys and smiles mischievously. ‘Well, Aunty, I did start to, but then . . .’

‘Hmm?’ Diana rolls her eyes. ‘My makeup bag proved more interesting?’

‘You shouldn’t have left it out, Mam, you know how easily distracted I am.’

‘You’re a cheeky one, Gracie,’ laughs Violet.

The wireless announcer forms a fourth companion at the table; a rich male voice from London that sounds clothed in tails and a white bow tie and dress shoes from Bond Street. The tinkle of their knives and forks merges with sonorous choral music and the clang of bells ring ing, from Big Ben to a medieval kirk at the furthest reaches of the Hebrides. The land beyond their dining room is in mourning, the stars frozen in their stations, the moon shrouded in black.

‘Take these dishes to the kitchen, then get ready for bed, Grace.’

‘Yes, Mammy.’ Grace swigs the last of her raspberry cordial and then organizes as many plates as she can in her arms, as she has seen the waitresses in Betty’s café do. ‘One at a time, you can’t carry all of those,’ says Diana, relieving her of some of the pile and following her into the kitchen.

Violet is desperate to lie flat in her bed and fall asleep but she still has to write up the day’s takings, secure the front door – upper and lower bolts, two deadlocks, Yale lock – and then the back door, before carrying the metal cash box up to her bedroom. The weight of it all pins her to the chair before she forces herself up and walks mechanically back into the adjoining shop.

Even at this late hour music pounds through the walls from the Maltese boarding house next door ‒ rock ’n’ roll with insinuating saxophones and thrusting drums ‒ and Diana bangs her fist against the plaster to make them quiet. An explosion during her time with the WAAF in the war has deafened her a little in one ear but the Maltese play their music loud enough to wake the dead. With her daughter asleep in bed, Diana changes into her nightdress and slips under her quilted silk eiderdown. It was Violet’s wedding present to her, and for some reason one particular corner still smells of Ben’s cologne. The night always makes the presence of him blur his absence. She draws out his journal from under her pillow and holds the small blue pad carefully to stop loose pages falling out. The lamplight makes the pages look translucent, his fine, even handwriting floating in the air like a chain of dragonflies.

She blinks twice and brings the journal closer to make the words still. The entries have stopped reading like the words of a dead man and instead allow her to believe that he is still out there, in Egypt: sheltering from sandstorms, wandering through the souks of Suez and Bardia for souvenirs to bring home, before the nighttime sorties in the Wellington with ‘his boys’ in 38 Squadron. She hadn’t realized before the war what a beautiful writer he was. Even his empty days, spent reading whatever books he could get his hands on, were written in a way that made her feel the stifling languor of his tent. Now, the deserted Italian positions littered with abandoned trucks, motor cycles, jackboots and binoculars are as familiar to her as the steam-powered fairgrounds of her childhood. The mercury incandescence of the Mediterranean lit up by a full moon more worthy of a place in her memory than the turgid Irish Sea.

It takes Violet a moment to understand what the sound is. Her nightmare is still live, filling her mind with images of hands banging on the windows of a synagogue as the entire white structure sweeps up into flames, the night sky shimmering green and blue from the Northern Lights, the cries of men, women and children lifting up to it unheeded.

An alarm.

An alarm ringing.

Not for those dying inside the shul, but for her, in her own home. She sits bolt upright in bed and holds her head in her hands, her heart pounding louder than the metallic rattle of the burglar alarm. Edging her feet into her slippers, she picks a silver candlestick up from the dressing table and switches on all the lights. Hearing footsteps on the landing, she holds on tight to the door knob and feels almost ready to faint. It would be easier to just die here quietly, she thinks, than to face whatever is on the other side. Leaning her forehead against the door, she closes her eyes and slowly turns the knob.

‘It’s alright, Violet, the window’s busted but there’s no one down there.’ Diana is standing at the top of the stairs, a torch in her overcoat pocket and a hammer in each hand. Seeing her sister’s bloodless face, she stomps over and pulls her into her arms. ‘Don’t be getting into a state, Sis, everything’s fine. Whoever it was chickened out.’

Shaking, Violet holds on to Diana and tries to gather her nerves together; it’s not just the break-in, or the one before, or the one before that, but the letters that land on the doormat, counting the relatives murdered in Eastern Europe. Names that she barely remembers from her childhood, figures she can just about identify from black and white family portraits now come to her in her dreams, crowding her dining table and asking for more food, more water, a place to rest ‒ please, please, please ‒ pleading with her in Polish, kuzyn, ocal mnie, cousin, save me. Nowhere feels safe any more, it is as if the world is trying to sweep her away, her and everyone like her, creeping through locked doors and windows to steal the life from their lungs. Avram dead, Chaja Dead, Shmuel dead. In Lithuania, in Poland, in Germany. More and more names to add to the memorial plaque at the Temple. The facts still seem unreal. How could they all go? The letters from Volackis in New York and London pile up but make less and less sense, rumours of who perished and where, when and how, a drip feed of death with a little happy news forced in at the end ‒ a birth in Stepney, a graduation in Brooklyn.

‘Which window is it?’ she finally asks.

‘The little one around the back. We’ll call Daniel in the morning and get him to brick it up. I’ve put boxes up against it for now. Come on, get in with Gracie, and I’ll keep an eye on things.’

Nodding obediently, Violet creeps into her niece’s room and slides into bed beside her; gathering the child’s sleeping body up in her arms, she feels even smaller and more vulnerable than her. There is an atlas on the floor beside the bed and Violet reaches for it, flicking through; the red of the British Empire tints the pages. She’s had to learn so much more of the world recently, learnt the names of places that sound fantastical – Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Manchuria. The strong young men and women who had hidden in forests and survived Hitler are scattered, running, running, running from the catastrophe, going further and further east, as if looking to jump off the edge of the world. It’s become the work of spinsters, who don’t have the excuse of husbands or families, to round up these waifs and strays, these communal children who trust no one but take whatever is given. She sends money to these distant relatives and even to their destitute friends through banks in Amsterdam, Frankfurt, Istanbul, Shanghai, never knowing if it has got to them in time, or if they will come to their senses and turn back to civilization, if it is still that. Violet drops the atlas back on the floor. The rhythm of Grace’s inhalations and exhalations calm her but not to the point of sleep; her ears are fixed on the sound of Diana sweeping the glass away down stairs, her feet marching up and down the floorboards, fearless and strong, until finally she pounds up the stairs as the first birds call up the dawn.

Daniel arrives while they are eating breakfast, the fear of the night veiled by the homely scents of coffee and toast. Violet blushes as he leans over to grab a crust from her plate, his deep, foreign-accented voice thrilling her and his bearlike body filling the dining room. She snatches a glance at his pale, wide-eyed face lost in the black fur of his beard and astrakhan hat, crumbs catch ing in his moustache. Musky cologne emanates from his damp sheepskin coat as he pulls it off and hangs it up in the hallway. He belongs to Maggie, their middle sister, but desire and envy have crept into Violet’s heart. Her body is flush with yearnings stronger than she has ever felt before, and Daniel is the focus of them, his tall and broad frame like a sepulchre for her hope of some day bearing children. He is in her waking dreams: his lips, his hands, his pink nipples lewd and raspberry-like against his snowy skin. The fire in her womb suddenly flaring before the change moves the heat somewhere else. She looks forward to the end of it all ‒ anything rather than this lovelorn, girlish infatuation with a man who sees her as a sister.

‘Maggie is worried about you girls, she thinks the street is getting worse. I tell her it nothing, cost of the business, but she like a chicken this morning, pacing, pacing. She wants me to get you a gun!’ Daniel pulls up a stepladder and eases the remaining glass out of the window frame. ‘It must have been a little fella who think he can come through this window.’

With his back to Violet, she cannot help but look at his backside straining against his trousers. She looks quickly away when she sees Diana smiling at her.

‘No need for that,’ Diana replies. ‘Me and Vi have agreed that we couldn’t stab a burglar but we could certainly batter one. Vi came out of her room ready with a candlestick last night, I’m sure she would have made mincemeat out of him.’

Daniel’s laugh booms out and then it’s just the grind of mortar mixing, the scrape of metal on stone, and the tap-tap of bricks piling one on top of the other. The rectangle of light quickly extinguished and another barrier placed between the world and Violet.

After Daniel departs for the gentleman’s outfitters he owns with his brothers on Church Street, Grace kisses them goodbye and strolls the few minutes to St Mary’s primary school, which sits beside the church where most of the locals are baptized, married and laid to rest. Diana sets up her table as a turf commissioner in the small, damp outbuilding in the yard, the radio turned on to follow the day’s major racing fixtures. Her nails, painted so thickly scarlet they look dipped in vinyl, are the only colour in the room. Her face will be slowly made-up throughout the day, like a photograph developing in a darkroom, until at 5 p.m. she will look ready for a red carpet; the transformation from young widow to aged starlet complete. Violet, on the other hand, is habitually barefaced and clean-nailed, she wears a simple navy calf-length dress and her father’s silver war badge pinned to her brassiere for courage.

One display is still how their father left it; full of expensive compasses and ivory-inlaid hipflasks that are beyond the reach of their customers but still distinguish the shop from the others on the road. The rest of Volacki’s is engorged with cheap and popular items: wellington boots hanging off hooks, black school plimsolls crammed into wooden cubbyholes, cotton dresses hanging ethereally from a rail near the stockroom, wool en blankets wrapped in tissue paper and stored on the upper shelves. This shop is a ‘padded cell’ in Diana’s eyes, a place of madness whose method only Violet knows, the merchandise piling around her in small, unstable heaps. She sells knives, razors, rope, oilskin hats and coats, good strong work boots, sea bags, pipes, tobacco and snuff, but the real money is in cashing advance notes of pay for departing sailors. The heavy hand-cranked till collects more than a hundred pounds a day in its deep trays ‒ and is only touched by Violet ‒ never mind the safe or drawer where she keeps larger notes. The last customers arrive after the official closing hour, knocking discreetly yet impatiently on the glass panels to buy an urgent box of matches or cigarettes; everyone bending the law a little to make life easier.