I’d been dreading going to Nebraska for most of the summer. My trip was set for mid-August, just two months before the ten‑year anniversary of Elissa’s death. In the first few years after she died, any tether to Elissa on the calendar—her birthday, the day she died at just eighteen years old, the date of her funeral—would derail me. But as more time passed, I started feeling like they no longer warranted a breakdown.

Now I was twenty-eight, living in New York City, and working in journalism. The life that I’d been manifesting ever since Elissa and I were children had materialized. And while I felt a profound pull to go to Nebraska, to visit Ponca Pines Academy, the place where Elissa spent her last school days, my fear over what the experience might elicit was even more potent. It could unleash the deeply buried grief that still gnawed at me. Unresolved and uncomfortable.

Elissa and I were infants when we met, going on to attend nursery, elementary school, and temple together. Elissa wasn’t just my first friend; she was my favorite friend. She was boisterous, unabashed, brazen. In first grade, I sheepishly showed her the wart on my finger I’d been hiding underneath a Band‑Aid, only to have her rip her shoe off and expose the ones that lined the bottoms of her feet. When my breasts blossomed before hers in fifth grade, she wore a bra alongside me in solidarity.

By seventh grade we’d started partying together, stealing coconut rum from the bar at my grandmother’s house and taking swigs before logging on to AIM, tipsily IMing our friends and crushes. We shared these early acts of rebellion before our paths diverged, before Elissa was sent away to Ponca Pines, and I stayed behind, forced to forge my own identity within our hometown.

Ponca Pines wasn’t a traditional high school. It was a therapeutic boarding school and part of the Troubled Teen Industry: a network of private, unregulated residential programs that some fifty thousand teens will attend each year in their parents’ hopes of quelling their bad behavior.

A fact I was unaware of when Elissa was first sent there, but has since come to consume me, still unable to shake the feeling that something must have happened while she was in the school’s care, that the time she spent away from the world we co-inhabited, the life we seemed to share, somehow, someway, contributed to the fate that befell her within a year of graduation.

When I finally arrived at Ponca Pines, the school had long since closed, but I was happy to discover I could still walk freely around the fields of sun-bleached grass Elissa had once traversed. I envisioned Elissa everywhere: in the campus’s abandoned, untouched stretch of buildings, painted in a coat of white so old that it was peeling off in sheaths; sitting on the wraparound porch of the residence, or beneath its sloped roof, which gives the house the appearance of a ski chalet; hanging out alongside the other classmates of hers whose lives had also come to consume me: two girls uncannily named Alyssa and Alissa.

I first discovered Alyssa and Alissa on Elissa’s Facebook page; in the days after she died I’d taken to her profile with a fury— looking for solace in the litany of pictures, prayers, and memories that had come to populate her wall—but all I could focus on were the messages from Alyssa and Alissa. Messages like Elissa taught me what it was really like to have a best friend … Love you always Elissa. Save our souls.

Save our souls. The first time I glimpsed the phrase was on Elissa’s body when she showed me the tattoo she’d gotten shortly after leaving Ponca Pines: those three words penned on her ribs in a Comic Sans-esque font. Then I saw the phrase again on Alyssa’s and Alissa’s bodies. Save our souls inked in cursive on the outside of Alyssa’s left hip, and stretched across Alissa’s back, horizontally, over a broken heart with angel wings. The eerie expression deepened my fascination with the girls. And by 2019, you could call it an obsession. By that year, both of their walls had also become memorial pages. Alyssa passed away at twenty-three, and Alissa died four years later, at twenty-six.

Elissa, Alyssa, Alissa, and I were all the same age, and all born into similar circumstances. We lived in suburban communities and were raised by parents with means and access. The four of us all started acting out in middle school and high school. Smoking weed, drinking, dabbling in pills. Rebellious behaviors that were of the socially acceptable, suburban variety—until they became something greater, more fearful. Considering this, I started to wonder, Why are these girls no longer here? Why am I the one left telling this story?

The Elissas is a look at my journey of trying to grapple with how our lives could have gone in such radically different directions. In writing it, I’ve interviewed more than sixty people in relation to the girls. I’ve spoken to those who represent the many facets of the Troubled Teen Industry. Students who feel as if the industry made a positive impact upon them, as well as those who identify as survivors and allege that they suffered abuse and neglect at these programs. Practitioners of these programs, as well as experts, journalists, and community advocates who research the effects of the industry.

I’ve talked with the girls’ friends, romantic partners, classmates. Those they met in the various troubled teen institutions they attended, or the treatment programs they enrolled in once they were no longer teens. People who have recovered from their addictions, along with young adults who still actively use. I also developed relationships with their parents and families, who I’ve come to believe were just as much victims of this industry as their daughters were. And while some opted to remain off the record, they still supplied me with notes about the girls’ lives.

When I finally set out to write this book and tell their story, I knew I couldn’t do it without resolving something in me: I had to see the Ponca Pines campus. Though it closed in 2012, there are many other institutions around the world like it, and I was still hungry to inhabit the space. Going there called to me, as if I could breathe Elissa’s recycled air.

While there, I sat on the swing set where the girls would convene to gossip. There were six swings in total—three were low-hanging ones and another three sat about a foot higher off the ground—all of which gently rocked back and forth to the rhythm of the air. I gravitated to a lower one, and as I started swinging on it, all I could think about was an imagined retort from Elissa. You’re such a pussy, Sami, she’d tease after inevitably taking a higher swing. I thought about what Elissa, Alyssa, and Alissa must’ve looked like on the swing set together. Picturing the girls laughing loudly, in motion, the words started coming to me. Sketching them into a scene I could already see in my head, I kept pumping, smiling, gripping the chains. Going higher and higher in the air.

____________________________

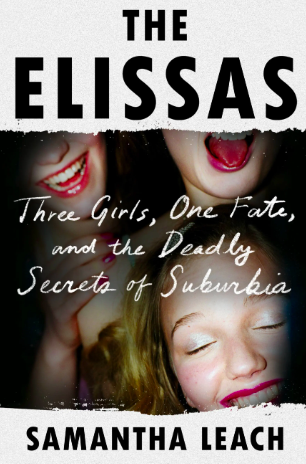

Excerpted from The Elissas: Three Girls, One Fate, and the Deadly Secrets of Suburbia. Copyright © 2023 by Samantha Leach. Reprinted with the permission of Legacy Lit.