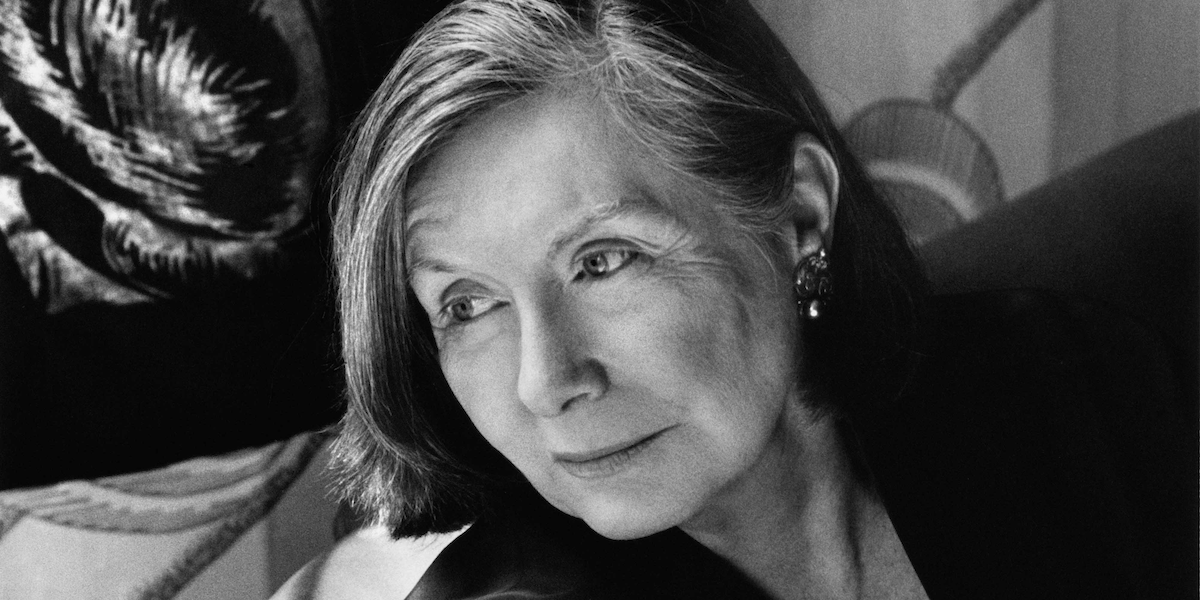

Image courtesy of Marion Ettlinger.

Maureen Howard, an author of adventurous fiction and a prize-winning memoir, and an esteemed teacher of creative writing, passed away on Sunday in New York City. She was 91 years old.

Howard was the author of ten novels, three of which, Grace Abounding, Expensive Habits, and Natural History, were finalists for the PEN/Faulkner Award. Her 1978 memoir, Facts of Life, was the winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award. She also edited The Penguin Book of Contemporary American Essays (1984). Among other honors she was the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship and an Academy Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and letters.

Howard was, in the words of Anne Tyler, “a most agile, inventive, and satisfying writer” who was always seeking new ways of telling stories. “Why Howard isn’t cherished more is mystifying,” wrote John Leonard in a front-page New York Times review of her late novel Big as Life. “It’s as if, while nobody watched, Mary McCarthy had grown up to be Nadine Gordimer, getting smarter, going deeper and writing better than ever before, and she was already special to begin with.”

Many considered Howard’s masterwork to be her 1992 novel Natural History, a family chronicle that incorporated drawings and photographs, in which Howard took Bridgeport, Connecticut as her Dublin. In a front page review in the New York Times Book Review, John Casey wrote that “it is the combination, the jump-cuts, and layering and dovetailing of fiction and history and of a variety of voices that make reading this novel like watching a display of the aurora borealis.” Later in her career, Howard produced a boldly structured quartet of novels published by Viking Penguin (A Lover’s Almanac, 1998; Big as Life, 2001; The Silver Screen, 2004; and The Rags of Time, 2009) that critics praised as “brazenly intelligent” and “raptly adventurous” works of “historical density and deep emotional power.” Each of the four novels was complete on its own, but characters and themes were woven across the cycle as a tapestry of seasons.

Howard was born and raised in Bridgeport, Connecticut, and educated at Smith College. Her first novel, Not a Word About Nightingales, was published in 1962. A second novel, Bridgeport Bus (1965), told the story of a beguiling Irish-American woman who leaves the emptiness of small town life in Bridgeport for the maelstrom of Manhattan; Doris Grumbach called it “one of the most astutely funny novels of our time.” Beginning in the late 1960s, Howard taught writing at several universities, including Rutgers, Princeton, Brooklyn College, The New School, the University of California at Santa Barbara, Yale and Columbia.

A memorial is planned for the spring.

–Paul Slovak, Vice President and Executive Editor of Viking Books

*

Maureen was my writing teacher nearly thirty years ago. She changed my life, with her kindness and advice, her keen encouragement when the chips were down. And her books—in a way that I’ve only become conscious of recently—left an imprint on my own way of constructing fiction. Maureen had a four-dimensional understanding of story, reliably shuttling between points of view and points in time, keeping the folded clock (to use my classmate Heidi Julavits’s term) ticking, deploying various forms to tell the story fresh, keep readers on their toes: diary and playlet (Bridgeport Bus), triptych (Big as Life), double entry ledger (Natural History), the titular tome of A Lover’s Almanac.

Even before she slipped away last week, I had a copy of Natural History, Maureen’s magnum opus from 1992, on my writing desk, as a beacon to see me through the complicated novel that I am revising. See, the book whispered to me, it can be done! After she passed, I opened the book, to find four pieces of printed matter, haphazardly preserved years ago, now as fascinating as glacial debris. (I think she wouldn’t mind the joke Moraine Howard.) What would Maureen do? I could imagine a whole book told through these documents, Howard-style; for now, here’s a brief annotation, in the magpie spirit of her work.

A) Mauve bookmark from the defunct Bailey/Coy bookstore on Madison, on the back of which I’ve written, in a tiny hand, “27 mibs.”

A mystery. I turn to page 27, which happens to hold a perfect noir passage that’s typical Maureen—language imbued with memory, hewing to its own rhythm:

It wasn’t a belle puffing smoke at him from the pouty lips, the restless desire in her eyes practiced on a hundred bar stools, or, what the hell give her the benefit of the doubt, verandas. Eyes shallow as mibs, the pale brown shooting marble James lost down the backseat of the car. Eyes not pretty but useful and she gives that tough mib look to Billy Bray, the luster worn off it years ago, passing it around just as natural as trying for a breeze, the eyes and mouth searching him as she has searched the soldier boy last night, wanting something for herself.

That shrugging “verandas” makes me laugh. “Tough mib look” is lucid and accurate; it’s also a word combination so weird it also makes me laugh. Now imagine almost 400 pages of such pleasures.

B) Invitation for a February 19, 1998 event at the PEN American Center—Maureen in conversation upon the publication of A Lover’s Almanac. It’s the sixth installment of “The Writer, the Work,” a series of “encounters with world literature,” curated by Susan Sontag.

The description sounds like Sontag in her best superlative register. “Maureen Howard is writer in a heroic American mold…[who] has explored the complexity of our dreams and of private life…[O]ne can only wonder why this extraordinary body of work does not figure more centrally in the usual accounts of American literature.”

Isn’t it time?

C) Printout of my introduction to her 2005 event at the 92nd Y, where she read from The Silver Screen, sharing the stage with Cynthia Ozick.

This is the sole surviving copy of the text, most of which I’ve forgotten, save for the line: “As the Koreans have been called the Irish of Asia, it’s perhaps small wonder that we became friends.” A good line: “Now, if you’re going to name a character Artie Freeman [a key figure in her career-ending tetralogy], you’d better be prepared to make your own art a model of freedom. And of course, Maureen does.” Also, I compare one character’s surprise reappearance to that of John Travolta’s character in Pulp Fiction.

D) Toast-shaped, lemon yellow business card for Columbus Bakery, 474 Columbus Avenue.

The whimsical logo of this now defunct eatery depicts a happy slice of bread toting baguette, wearing chapeau, yet this is the document that makes me sob. Save for a spell on the East Side, I’ve basically lived within ten blocks of the apartment where Maureen and her late, wonderful husband Mark resided on Central Park West. In the late 1990s, I lived in a small studio on West 83rd Street. Most mornings I would go to Columbus Bakery around the corner, to write what would amount to my second unpublished novel. (Longhand—no laptop in the 90s.) Maureen would often meet me there, buy me a pastry, basically make me not feel insane.

I loved her so much.

–Ed Park

*

Maureen was my only writing teacher, and after I studied with her, I never looked for another. She was precise, impassioned, impatient, not exactly satisfied with anyone’s work, but sizing us all up, it seems to me now, as possible writers, or at least as cocktail-party invitees. Maureen lived in writing constantly. She hurried (I remember her hurrying) between the study in the back of her apartment and the sofa in the front, the New York Review, a glass of gin, a bowl of nuts, a conversation about someone else’s first novel—good, good, but perhaps one could do better? Inviting an awkward ex-student to think: perhaps me? I don’t know if my books met her standards, but she did keep having me over for drinks. Her hospitality was flawless, and, like many other things about her, it said, Let’s get to the point. What are you reading?

As for what happened when the guest went home and Maureen hurried back to her study, we have her books for evidence: keen-eyed, encyclopedic, often waiting for you to catch up. Reading them, you might think that Maureen wanted everything to go into a book sooner or later, but I wonder if it would be more accurate to say that, for Maureen, everything—students, walks, cocktail nuts—existed so that there could be books, and people who loved to read and occasionally write them.

–Paul La Farge

*

Maureen had a capacious intelligence, and she was generous with its expression. She got on with her work as a writer without a lot of fanfare. She did what the greatest artists do—stretched available forms to their limits. In the process, she made everything interesting. All she had to do, it seemed, was tell what she was thinking.

I’m reminded of a couple of pages deep inside her last book, The Rags of Time, when the narrator is thinking. That’s it. She’s thinking, and it’s powerfully gripping. She thinks about a garden in the Berkshires. She thinks about the building where she lives, across from Central Park. She thinks about the war in Iraq and the lies of politicians. She thinks about her mother cutting a piece of navy cloth for her brother’s confirmation suit. She thinks about her own responsibilities and privileges. She thinks about her beloved grandchildren and a tropical fern in their terrarium. She thinks about reading and writing and the books on her shelf. At this point, with her thoughts roaming across literary history, they land on Don Quixote, and it’s like a key turning in a lock. The door swings open and we get a glimpse of the driving purpose that powered Maureen Howard through her long, magnificent career:

I’m still mad as Quixote, the spindly knight. Lost in the tragedy of my bookishness, I share with the Don the illusion that tales are the true documentation of life.

Mad… lost… tragedy. It all sounds dire, but there’s a slyness behind the lament. The passage may begin with madness, but look at how it turns tragedy upside down and moves from illusion to truth, from bookishness to life. For this teller of tales, this writer who, I wager, will be among those still read in a hundred years, life is best understood when we’re given the chance to document it, imaginatively and with artistry.

As for being as mad as Quixote, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. It takes me back to a line from a chatty email Maureen sent me twenty years ago:

Finishing the semester. Mad to get back to the sanity of work.

(She sure could tell a good joke. In that same email, in response to my complaints about the challenges of writing and publishing, she wrote, “Think of a plot for a best seller and I’ll hammer it out.” Damn—I never came up with that plot.)

It was a privilege to be Maureen’s friend and share with her the wonderful illusion that tales are worth telling. When I reread her books, I keep seeing how much I missed on the first reading and am grateful for all there is to learn. I remember when she started to talk about her vision of a set of interconnected books organized around the seasons. I remain astonished at her ability to conceive of such an ambitious project in its totality and to see it through over the course of more than a decade. There were times when she worried about its prospects, but she kept on, quietly undaunted, modest and yet fiercely dedicated to making her art.

Maureen looked hard at the world in her effort to document it. She did what she could, through her writing, to make people aware of injustice and degradation. She also wanted to give readers reason to be fascinated. She herself was fascinated by acrobats, magic tricks, birds, almanacs, maps, old photographs, new photographs, the past, the present, Bridgeport, Connecticut, and New York City. I think the place that fascinated her most, outside of the space of her elegant apartment, was Central Park. She made it her mission, through multiple books, to document the beauty and history of the park.

In Rags of Time, amidst all the thinking the narrator is doing, she tells us about sneaking out of her apartment building without a coat, hat, or scarf, to go for a walk in Central Park. It is winter in this fourth book that completes the four seasons. “Snow fell gently, translucent on the pavement.” It is slippery in the park, but still the narrator manages to climb up the slope to the Reservoir Track. She takes in the scene. She looks down and sees an image that encapsulates the purposefulness of Maureen Howard’s artistry: “All I want: my footprint in the first snow of the season, faint proof that I still venture.”

She leaves behind her tales full of brilliance, documenting moments in time, there for an instant, and still there, long after the snow has melted.

–Joanna Scott

*

Maureen Howard was a bold, adventurous writer of the first rank who loved the idea of making the novel do and hold more. Her fiction was innovative and exploratory, but it was also intimate, personal, and vivid. I always thought of her as a kind of Smithsonian, recreating America of the 20th century through collecting and curating endlessly resonant, dense details. Her mind was both tender and satirical. She saw and remembered everything. In a work like Natural History, she perfected a profound microscopic-macroscopic style built out of supple sentences that leveraged all the senses. She was the best of modernism wedded to a timeless introspection.

She was also the most generous and tireless benefactor of other writers that I’ve ever known. Maureen helped me and other writers of my generation get established, and she spent tireless hours reading, reviewing, discussing, teaching, and promoting the literature that she most admired. No one I know has done more for American letters.

–Richard Powers

*

Maureen began as my teacher and mentor at Columbia and became my dear friend, and my life would be very different if she hadn’t been all of those things. When I was writing my first novel, I reached a point where I was scared to continue with it. After months of dithering, I expressed my doubts to Maureen. She said, “Nonsense. You mustn’t be afraid of your book. Just make damn sure you do it right.” Then, with a little wave of her hand, “And of course, you’ll do it right.” I loved that fierceness she had, when it came to what she called The Work (I always heard it in capital letters when she spoke of it—I’m sure I’m not alone in that). For Maureen, writing was of the utmost importance, and so when she believed in you and your work, you began to believe in yourself.

I was lucky enough to live across the street from Maureen and Marc for a time, so I got to see them often. Their place was a hive for writers, and there were always a bunch of us buzzing around, for drinks and dinners. Maureen’s interests were far-ranging, and she brought her ferocious intelligence and wit to any topic. She had a disdain for flavor-of-the-month writers and posers of all stripes, and her take-downs were deliciously mordant. To her students and friends, she was supportive and generous and challenging in a way that made you want to be better. Knowing her was a tremendous gift for which I’ll always be grateful.

–Hillary Jordan

*

My favorite thing I heard Maureen say—to a student in a Q&A who asked naively but meaningfully what was the most important thing for a young writer to do: “The most important thing for a young writer is to affix the ass to the chair.”

–James Longenbach

*

How unlikely it would be to think of a way in which Maureen Howard didn’t affect many of us, as she did me and whatever I was doing, whenever and wherever it was. Early on in our blessedly long relationship, when she would come over and join a group of us, readers and writers and all graduates of Smith and Holyoke and Bryn Mawr, it would always feel, no matter where like home, and as if we had always been there together.

Way back when, I would go to her place down in the village for drinks and meeting always fascinating talkative types. Then, whenever it was, I knew her second husband David Gordon, as a colleague at the Graduate School of the City University of New York, for a few years. There, of course there, where else? (I am not prejudiced, having taught there so happily for fifty years) the all-embracing Alfred Kazin. When Maureen so brilliantly married Mark Probst, I would go over (frequently) to have dinner with them on Central Park West, and always loved reading his writing as well as hers, of which I read every single bit. I would sometimes spend weekends with them in the country, going with him to get various tomatoes and such in their village while she was writing.

In the city I would be taken along with them to brunch or lunch at the Café Luxembourg, and various celebrated personages would come up to greet and chat with Maureen, while I was always happy to sit with Mark and talk about whatever and whomever came up. In later years, my husband and I would go over to their apartment on Central Park West. I was amused, when we would be late after some musical event, she would say “we will be in the other room,” while I hadn’t figured out usually that the “other room” was the dining room, after the living room, where we would often meet other famous writers and poets like Richard Howard and many scientific and medical friends of theirs. At the dining room table, we so gladly would see Gloria Loomis, who was my agent also, and often other poet and scientific friends we knew through Mark and Maureen.

We’d go over for tea or drinks or lunch, where Maureen introduced me to those superb purplish Kumato tomatoes. I loved it when Loretta and her family would be there: always we, my husband Boyce and myself, felt family with Maureen and Mark. Years later, when Mark was in a wheelchair, Boyce and he would have lunch, or all four of us, on the same café on Columbus Avenue. And later still, I would visit her when I could.

I so heartily agree with Gary Davenport and my now gone friends Noel Perrin and Alfred Kazin, in saluting her warm in fact glowing intelligence and pen. She was the spirit of interconnectedness. When she was figuring out, for a illustrated book, the seasons and how to add the visual elements (not the dull stuff like permissions and all those boring if essential things) and how to have the relations both startling and subtle, I was excited to be somewhat involved. All my lengthy involvements personal and professional with Maureen Howard were, to me, something of a marvel.

–Mary Ann Caws

*

Maureen Howard was, along with such figures as William Kennedy, John Gregory Dunne, Robert Stone, Jimmy Breslin, Mary Gordon, her great predecessor (and, I suspect role model) Mary McCarthy and her great successor Alice McDermott, one of the most notable fictional chroniclers of the Irish American experience of the past century. (Stone’s uncertain parentage makes his actual ethnicity equally uncertain, but he sure wrote, thought and drank like an Irish Catholic, so I claim him for our own.) She was a brainy, astringent, exceptionally elegant writer, and she never made it easy on herself or her readers. She never stepped into the same narrative stream twice.

I had the pleasure of working with Maureen on two superb books. The first was the Penguin Book of Contemporary American Essays, a book assembled with such exquisite taste and judgment that, as I recall, even the impossible to please critic John Simon, was impressed. The other was perhaps her best known and certainly most ambitious book, Natural History. It was set in her native Bridgeport and, much like her fellow Connecticut writer John Dunne’s work, centered on municipal corruption, family ties, and a notorious crime. It was an immensely erudite book, presided over by the unlikely paired muses of Walter Benjamin and P.T. Barnum, and it truly earned this sometimes hackneyed encomium: She did for her native Bridgeport what James Joyce did for his native Dublin. The critics raved, and they should have.

Maureen and I were close for a while, possibly too close. We’d both made our way from unpromising and parochial (in both senses) backgrounds to fancy colleges and the New York literary world. We both had fathers who were big city detectives. I particularly admired her memoir Facts of Life—the best thing in its line, I believe, since Memories of a Catholic Girlhood—and I had read it as a sort of instruction manual on how to do this thing—become, I mean, someone other than the person you had been raised and expected to be. Our closeness was also related to the fact that she looked a good deal like my not particularly literary mother, both dark-haired and lovely, both fond but tough-minded in a watch-it-mister way. I always regretted that we drifted apart after I ceased to publish her.

Maureen Howard was, in every sense, a class act. Her books reward re-reading and are built to last. I’ll miss her, but those books are over there on my bookshelf and are coming down for renewed inspection right this minute.

–Gerald Howard

*

Maureen Howard taught me how to write books. She was my professor at Columbia University and one of the best I ever had. She was generous and insightful, wickedly funny and also quick to call out fools. As a writer she was elegant and stylistically daring, ambitious and big-hearted. I absolutely adored her.

–Victor LaValle