|

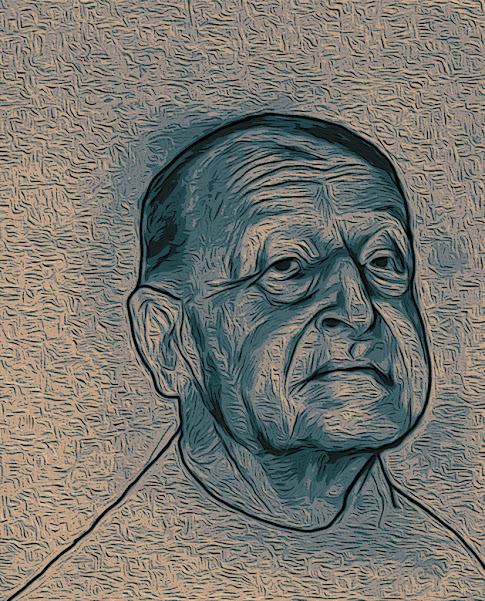

| William Somerset Maugham |

Collected short stories of Somerset Maugham

volume three

(17 stories)

Ashenden had a confident belief in the stupidity of the human animal, which in the course of his life had stood him in good stead. (Miss King)

Simon

March 28, 2018

In 1928 Maugham published Ashenden, or the British Agent, a book-length collection of linked short stories, told in the first person, about a British spy based in Switzerland during the First World War.

The stories are highly autobiographical. When the Great War broke out Maugham had volunteered to work in the ambulance corps and served on the Western Front for a year. In 1915 he returned to Britain to promote his new novel, Of Human Bondage, but then found it impossible to return to the ambulance work. His wife, Syrie, arranged for him to be introduced to a high-ranking intelligence officer, referred to in the stories, as ‘R’. (Syrie does not appear in of these stories.)

Since he came from a family of distinguished lawyers, with a father who had served in the Diplomatic Service, Maugham was deemed to be a good security risk, recruited and despatched to Switzerland in September 1915. He was one of the network of British agents who operated against ‘the Berlin Committee’, a German-funded spy organisation which had numerous projects afoot to undermine the British war effort. One of these was to encourage Indian revolutionaries to overthrow Britain’s colonial rule in India, a theme which has a long story devoted to it.

Maugham returned to Britain after a year. In June 1917 the British Secret Intelligence Service asked him to undertake a new mission, this time to Russia. He was to be part of an attempt to keep the Provisional Government brought to power in the February Revolution in power, and Russia in the war, by countering German pacifist propaganda. Two and a half months after he arrived the Bolsheviks staged their coup and seized control, ultimately signing a peace treaty with Germany.

The stories in Ashenden, or the British Agent are:

- R.

- A Domiciliary Visit

- Miss King

- The Hairless Mexican

- The Dark Woman

- The Greek

- A Trip to Paris

- Giulia Lazzari

- Gustav

- The Traitor

- Behind the Scenes

- His Excellency

- The Flip of a Coin

- A Chance Acquaintance

- Love and Russian Literature

- Mr. Harrington’s Washing

Volume three of Maugham’s collected short stories is devoted to the Ashenden tales, but for this republication he amalgamated the 16 short stories listed above into six longer ones. I can see why he did this, it makes the stories all about the same length, all long and meaty, and it gives a kind of weight to the book. He also added an additional story, Sanatorium, which doesn’t appear in the original 1928 volume.

Overview of the stories

Switzerland

- Miss King incorporates A Domiciliary Visit and Miss King

- The Hairless Mexican incorporates The Hairless Mexican, The Dark Woman and The Greek

- Giulia Lazzari incorporates A Trip to Paris and Giulia Lazzari

- The Traitor incorporates Gustav and The Traitor

Russia

- His Excellency incorporates Behind the Scenes and His Excellency

- Mr. Harrington’s Washing incorporates A Chance Acquaintance, Love and Russian Literature and Mr. Harrington’s Washing

Years later

The stories themselves

1. Miss King

Three pages describe Ashenden’s recruitment into the Service by ‘R’, described as tall, clever, dispassionate, his piercing eyes too close together.

Then we jump to a description of Ashenden returning to Geneva on the ferry which he uses once a week to pop across the lake to France to file his reports. In Geneva he discovers two policemen waiting in his hotel room. Technically, the French visits are illegal and they examine his passport and question him after having obviously searched the place in his absence. Ashenden knows he could face two years in a Swiss prison for illegal activities. He also knows that ‘R’ won’t lift a finger to help him. That’s part of the deal. His cover is that he is a writer (true) and has come to Switzerland to complete a play, a light comedy (also true). The draft manuscript of the play is on his desk and the Swiss detectives have noted it. They leave with no further fuss.

There are two further strands in this story: in one Ashenden spends a few pages facing down one of his operatives in Germany who’s insisting on a raise. Ashenden says like it or lump it but if you betray us things will go very badly for you.

Then the final part of the story gives us an overview of the hotel where Ashenden stays, and the cast of exotic guests – the Austrian baroness, the Egyptian pasha and his family and numerous other dubious characters – any or all of which might be spies like himself. Ashenden, in his lofty amused style, is considering having a flirtation with the Baroness, not just to fish for information but for the fun of it, however after a few days he receives a stiff message from London telling him to lay off. So, he realises – he is being watched!

In the middle of the night he is woken by the hotel staff and asked to come to Miss King’s room. The tiny old lady has had a stroke and cannot speak. Her little black eyes are trying to tell him something. He promises her he will stay with her. Completely separate from any considerations of espionage or the war, Ashenden or Maugham wins our respect for his humanity and compassion. He stays with her till she dies.

2. The Hairless Mexican

‘R’ calls Ashenden to the French city of Lyon to brief him (over a characteristically luxurious meal) that a Greek agent, Andreadi, is travelling from Greece to Brindisi in Italy with documents for German intelligence.

He then introduces him to an extraordinary character, the larger-than-life Mexican Manuel Carmona, who insists on being referred to as ‘the General’ and immediately starts recounting stories of his heroic deeds in Mexico where he would have been the next Minister of War had it not been for the present government which had him arrested, but he escaped etc. But all this is to overlook his main feature which is that he is completely hairless; he wears a wig and his eyebrows are painted on.

Ashenden is to accompany the Mexican to Italy, where they will split up, Ashenden going to stay in Naples while the Mexican meets Andreadi off the Brindisi ferry and brings him to Ashenden. For the purpose of the trip Ashenden has the cover name ‘Somerville’.

The point of the story isn’t at all Andreadi or the papers, it is Ashenden’s bemused reaction to the Mexican’s absurdly larger-than-life speech, manner and behaviour. He nearly misses the train to Rome, he shows off his knife and revolver, with swaggering stories about how he used both, when he takes Ashenden for a meal at a low dive he immediately chats up and dances with the prettiest hooker in the joint.

After a prolonged description of this preposterous character there is an eventual sting in the tail of this story, but you’ll have to read it to find out.

3. Giulia Lazzari

Called to Paris, Ashenden is briefed by ‘R’ at another characteristically swanky restaurant. The most important Indian nationalist – Chandra Lal – the leader of the group which has been organising unrest and bomb attacks in India with a view to distracting British forces from the Western Front, is coming to Europe, specifically to Switzerland, to pass on information to German agents there.

‘R’ tells Ashenden that Lal has fallen in love with a dancer – Giulia Lazzari – an entertainer, a courtesan who he met in a cabaret in Berlin. MI6 tracked her across Europe and arrested her when she came to England. Searching her belongings they discovered passionate love letters from Lal. Ashenden’s mission is to accompany Lazzari back to Thonon on the French side of Lake Geneva, and do whatever is necessary to force Lazzari to persuade Lal (by letters) to cross the lake and visit her. Lal will be arrested as soon as he steps on French soil.

And this is just what happens. The interest isn’t in the result, it is in the interaction between Ashenden and Lazzari; it is in his simultaneously clinical use of her and his odd, detached compassion.

4. The Traitor

In the first part Ashenden goes to Basel to check on one of his most successful agents inside Germany, the spy ‘Gustav’ who sends detailed accounts of troop movements and so on. He is not all that surprised to find him at home with his wife despite having just despatched a ‘top secret’ message from Mannheim. Without much pressure, the ‘spy’ admits that he’s been living in his nice apartment with his wife all this time, making up his reports from newspapers and magazines.

In the second part Ashenden is sent to Berne to get to know a boisterous Englishman, Grantley Caypor, living in a hotel there with his grudging German wife, who MI6 now have proof is a spy and a traitor, for he is sending German High Command information for a salary of £40 a month.

Again, the interest isn’t in the ‘story’ as such, it is entirely in the depth and detail with which Maugham depicts this character, big bluff and jovial, a hearty walker in the mountains, interested in botany and boyishly devoted to his ugly bull-terrier.

‘R’ has instructed Ashenden to use the cover name Somerville again and to put about a cover story that he’s recovering from an illness and had previously worked in the British Government Censorship Office.

‘R’s plan is simple. He knows the censorship story will get back to Caypor’s minders; he knows they will immediately think of using ‘Somerville’ as a way of getting Caypor into the Censorship Office, too good an opportunity to miss.

And so it comes to pass: with suddenly frightened eyes, Caypor asks ‘Somerville’ for recommendations to his superiors in London which ‘Somerville’, acting all artless and helpful, writes for him, and Caypor reluctantly sets off to France and then to London. He doesn’t want to; he knows the risk; but his German minders have obviously forced or even blackmailed him into doing it. And Ashenden knows all this.

Every day Caypor’s tight little German wife goes to the post office expecting the letter he’d promised to send when he arrives safely. But it never comes and ‘Somerville’ knows why. Caypor will have been arrested on reaching British soil, tried and executed as a traitor. Ashenden envisions the scene, the grey morning, the blindfold, one member of the firing squad throwing up, the officer stepping forward to fire the coup de grace.

The ‘interest’ is in Maugham’s clinical observation of Caypor, noting every detail of his quirks and characteristics, pondering the One Big Message of Maugham’s fiction which is that People are More Complicated Than They Seem.

5. His Excellency

The Russia stories dramatise Maugham’s second mission, to Russia, between the March revolution and the Bolshevik coup in October.

The first one describes Ashenden’s encounters with the British Ambassador to Russia, initially rather frosty, but which slowly warm up until the Ambassador invites him to dine in the extraordinary splendour of the British Embassy.

No summary can convey just how incredibly posh and upper class this meal is, both men dressed to the nines, at a small dining table in the vast dining room designed to hold 60, festooned with paintings by Old Masters, gold candelabra. In this setting Ashenden tells a story-within-a-story, about a successful British diplomat they both know – Byring – who threw away his career after falling in love with the most famous courtesan in Europe.

Before I started reading his short stories I had the impression that Maugham was the poet laureate of colonial life in the Far East, but there turn out to be far more stories about swanky meals at posh restaurants in London or very, very upper-class dinner parties at which the narrator tells or hears stories about the very highest in society. Although he is at pains to depict himself as an outsider, as a writer only admitted for his fame and not really a part of this society, nonetheless this is Maugham’s real milieu.

Stepping back from the details of this story, it is staggering that Maugham was in Russia during the most exciting months of its history, and yet that his longest, most intense story about being there is an account of a very formal dinner with the unutterably upper-class ambassador at which neither of them even mention the War or Russian politics.

Instead the discussion of Byring’s foolishness leads on to the best thing in the book, which is a long monologue in which the Ambassador reveals that he himself had a rash and foolish love affair when he was a young man without connections, with a penniless and vulgar circus performer. This doesn’t sound particularly promising but, in the ornate surroundings of the embassy dining room, with the candles flickering, the Ambassador becomes so electrified by his vivid memory of the past and by the one great love of his life that he is reduced to tears, Ashenden is mortified with embarrassment and the reader is absolutely transfixed. It is one of the most riveting things I’ve ever read. My heart was racing when it ended.

6. Mr. Harrington’s Washing

The scene completely switches to describes Ashenden’s arrival by ship at Vladivostock. Ashenden had (as Maugham did) crossed the Atlantic, taken a train across America then ship from San Francisco to Japan and then onto the East Russian port.

Here Ashenden boards the Trans-Siberian Express for the 11-day non-stop train journey to Saint Petersburg and the point of this story has nothing to do with espionage – Ashenden is cooped up for this entire time with the most boring American in the world, Mr John Quincy Harrington who talks relentlessly, in a dull monotone about his family, friends, the excellence of the United States, as well as describing in detail the plotlines of all the books he’s ever read, and on, and on, and on, till Ashenden feels like he’s going mad. It is a portrait every bit as exasperatingly funny as the ambassador’s story in the chapter before had been intense and moving.

Once he finally arrives at Petrograd the mood changes as Ashenden meets, contacts and sizes up the situation – namely the army is mutinous and the Kerensky government weak and on the verge of collapsing.

However, you shouldn’t be alarmed that too much seriousness will intrude on Maugham’s habitual sang-froid, his taste for the absurd and the self-deprecating. While Russia hurtles towards revolution, his hero spends time wondering whether it is best to write in the bath or on a train journey.

Ashenden had never quite made up his mind whether the pleasure of reflection was better pursued in a railway carriage or in a bath. So far as the act of invention was concerned he was inclined to prefer a train that went smoothly and not too fast, and many of his best ideas had come to him when he was thus traversing the plains of France; but for the delight of reminiscence or the entertainment of embroidery upon a theme already in his head he had no doubt that nothing could compare with a hot bath.

This leads into reminiscence about his ill-fated affair with Anastasia Alexandrovna Leonidov which is played entirely for laughs, with the naive young Ashenden behaving like Bertie Wooster to Anastasia’s cartoon impassioned-tragic Russian heroine. Their affair eventually comes to grief because of her insistence that she have scrambled eggs for breakfast every day, without fail. Now he meets up with her again, but it is purely business, as they both work together to try to prop up the government.

Then the Bolsheviks seize power and all Ashenden’s plans are smashed. In the days leading up to the coup, he had been deploying a few Czechs who had been assigned to him (they want Russia to stay in the war so that the Allies win the war so that Austria loses so that Czechoslovakia can be free of Austrian domination) and, despite his best efforts to shake him off, the irritating American Harrington has continued to pursue his damn fool task of getting a commercial agreement with a government which is on the verge of collapse.

On the morning of the revolution Harrington comes into Ashenden’s room where the latter explains the situation and says he better leave, and quickly. But Harrington insists on getting his laundry which he gave to the hotel servants the night before. Anastasia volunteers to help the foolish American and they quickly establish that the dirty laundry has been sent out to a laundry. Harrington sets off to get it, chaperoned by Anastasia who knows the streets.

They find the laundry, have a big argument with the laundress but retrieve the bundle of Mr Harrington’s precious shirts, suits and pyjamas, and are returning when a couple of armoured cars come zooming down the street taking pot shots at passersby. Harrington is shot dead instantly. When Ashenden finds his body, face down in the mud, his hand is still clutched round his bundle of washing.

7. Sanatorium

There are people who say that suffering ennobles. It is not true. As a general rule it makes man petty, querulous and selfish.

Sanatorium was published a full ten years after Ashenden. It has nothing to do with spies. Ashenden is sent to a sanatorium for tuberculosis patients in Scotland. Here he gets to know half a dozen or so of the patients, and becomes involved in their lives and hopes. It’s difficult to summarise, but the story is full of love and kindness and ends on a very moving note.

Being a spy

At several points the narrator points out on Ashenden’s behalf that espionage work is boring, not unlike that of a clerk in the City who turns up at his office every day and spends it going through paperwork. He uses this as the basis for a small aesthetic statement, pointing out that art is required to shape and give point to this mundane matter.

Fact, as I said in the preface to the volume in which these stories appeared, is a poor storyteller. It starts a story at haphazard long before the beginning, rambles on inconsequentially, and tails off, leaving loose ends hanging about, without a conclusion. The work of an agent in the Intelligence Department is on the whole monotonous. A lot of it is uncommonly useless. The material it offers for stories is scrappy and pointless; the author himself has to make it coherent, dramatic and probable.

Morality

1. Patriotism

Maybe what comes over most from the stories is Ashenden’s laconic, amused scepticism. I wonder if he was criticised at the time for a lack of patriotism. Certainly ‘R’ tackles this issue head on, saying he has two types of chap working for him, gung-ho, public schoolboy patriots who’ll stop at nothing to biff the Hun; and then cold calculating types like Ashenden, who aren’t all that excited about King and Country and regard the whole thing as an amusing game of chess. The thing is, ‘R’ knows that Ashenden’s type is just as useful as the gung-ho type, more so in the kind of quiet, observant missions he is sent on. They also serve who only stand and mock.

2. Against undergraduate morality

In our day and age when patriotism is not much discussed or praised, the keepers of culture are still obsessed with morality, it is just a different morality from old. In this respect I can see a thousand undergraduate essays being written about Ashenden’s obvious heartlessness in the way he exploits Giulia Lazzari or coldly observes Caypor, the man he knows he is sending to his death.

And as soon as you introduce a feminist perspective on Lazzari, or a post-colonial (i.e. race-focused) perspective on Chandra Lal, the floodgates would open and a million more essays pour forth, all of which condemn Maugham for not sharing the enlightened moral values of 2018.

Which is why discussing ‘morality’ doesn’t interest me. Debating morality suffers from two weaknesses or drawbacks: it is endless and so rarely arrives at a conclusion. And it is obvious.

Obviously, judged by ‘our’ standards, Ashenden is heartless and cruel in his treatment of both people. Obviously, judged by the standards of modern political correctness, he is sexist and racist. But should we be judging him by ‘our’ standards? Maugham himself anticipated all such moralistic approaches and explains:

Ashenden admired goodness, but was not outraged by wickedness. People sometimes thought him heartless because he was more often interested in others than attached to them, and even in the few to whom he was attached his eyes saw with equal clearness the merits and the defects. When he liked people it was not because he was blind to their faults; he did not mind their faults, but accepted them with a tolerant shrug of the shoulders, or because he ascribed to them excellencies that they did not possess; and since he judged his friends with candour they never disappointed him and so he seldom lost one. He asked from none more than he could give.

Maugham observes, it is for others to judge, if they feel the need. If the observation is so detached as sometimes to border on the heartless, well, that is the fault of the world and how people behave, not of the detached observer.

Part of the entertainment of the long chapter on His Excellency His Majesty’s Ambassador to Russia is the way you can’t help hearing the note of admiration in Ashenden’s voice at having met someone even more lofty and disdainful of humanity than himself.

Sir Herbert raised the glass to his nose and inhaled the fragrance. Then he looked at Ashenden. He had a way of looking at people, when he was thinking of something else perhaps, that suggested that he thought them somewhat peculiar but rather disgusting insects. (p.157)

But the accusation of heartlessness obviously rankled. So much so that he repeats his defence of his attitude ten years later in the final story, Sanatorium.

The conversation left Ashenden pensive. People often said he had a low opinion of human nature. It was because he did not always judge his fellows by the usual standards. He accepted, with a smile, a tear or a shrug of the shoulders, much that filled others with dismay.

Acceptance. Acceptance of each other’s weaknesses and folly. That’s what I find so missing in contemporary political, critical and social media discourse, where everyone seems so quick to call out, name and shame, humiliate and attack. Hard not to prefer Maugham’s slow, calm, accepting worldview and attitude.

Ashenden continued to read and with amused tolerance to watch the vagaries of his fellow creatures.

3. Murmurs

Maugham is a suave murmurer. The regularity with which his protagonists murmur a sentence crystallises their role – suave, sophisticated, urbane, detached, laconic, witty, barely speaking.

‘Death so often chooses his moments without consideration,’ murmured Ashenden.

‘In my youth I was always taught that you should take a woman by the waist and a bottle by the neck,’ he murmured.

‘Your hands are like iron, General,’ he murmured.

Ashenden murmured a civil rejoinder.

No need to raise your voice. Never any need to lose your cool.

Fattipuffs and thinifers (and blue eyes)

Having noticed in volume two of the short stories that a lot of Maugham’s characters fall into two pretty simple categories – Fat and jovial or Slim and handsome – I quickly noticed this dichotomy present throughout Ashenden. Thus Chandra Lal’s main feature is that he is fat and oily.

[The photo] showed a flat-faced, swarthy man, with full lips and a fleshy nose; his hair was black, thick and straight, and his very large eyes even in the photograph were liquid and cow-like.

The peasant woman who smuggles his instructions in from France when she attends the weekly market in Geneva is fat and jolly. The rich Egyptian in Ashenden’s hotel, the Khedive is ‘a little fat man with a heavy moustache’. He is attended by:

Mustapha Pasha was a huge fat fellow, of forty-five perhaps, with large mobile eyes and a big black moustache… He was exceedingly voluble and words tumbled out of his mouth tumultuously, like marbles out of a bag. (p.31)

The traitor Caypor is fat as we are relentlessly told: he has a fat face, fat arms, fat hands, and a fat chuckle.

In sharp contrast the good guys are lean and tall and trim. Take ‘R’:

He was a man somewhat above the middle height, lean, with a yellow, deeply-lined face, thin grey hair, and a toothbrush moustache. The thing immediately noticeable about him was the closeness with which his blue eyes were set. (p.9)

Of course, Rose Auburn, the epitome of the Bright Young Things who is the subject of the long conversation between the ambassador and Ashenden, is herself a model of the slender flapper.

She had an exquisitely graceful and slender figure, and her innumerable frocks were always made with a perfect simplicity.

And the piece de resistance of trim elegance is the exquisitely turned out Ambassador to Russia.

Ashenden, as he sat down, gave the ambassador a glance. He was beautifully dressed in a perfectly cut tail-coat that fitted his slim figure like a glove, in his black silk tie was a handsome pearl, there was a perfect line in his grey trousers, with their quiet and distinguished stripe, and his neat, pointed shoes looked as though he had never worn them before. You could hardly imagine him sitting in his shirt-sleeves over a whisky high-ball. He was a tall, thin man, with exactly the figure to show off modern clothes, and he sat in his chair, rather upright, as though he were sitting for an official portrait.

In his cold and uninteresting way he was really a very handsome fellow. His neat grey hair was parted on one side, his pale face was clean-shaven, he had a delicate, straight nose and grey eyes under grey eyebrows, his mouth in youth might have been sensual and well-shaped, but now it was set to an expression of sarcastic determination and the lips were pallid. It was the kind of face that suggested centuries of good breeding, but you could not believe it capable of expressing emotion. You would never expect to see it break into the hearty distortion of laughter, but at the most be for a moment frigidly moved by an ironic smile. (p.151)

Blue eyes

Blue eyes are genetically recessive, which means they are relatively rare. It’s estimated that approximately 8% of the world’s population has blue eyes. But not in Maugham’s fiction, where they are remarkably common. We have met ‘R’s blue eyes, above. Also:

The spy was a stocky little fellow, shabbily dressed, with a bullet-shaped head, close-cropped, fair, with shifty blue eyes and a sallow skin. (p.20)

The baroness has fine features , blue eyes, a straight nose, and a pink and white skin…

There was a little German prostitute, with china-blue eyes and a doll-like face… (p.27)

Mrs Caypor has blue eyes.

Rose Auburn, the heroine of the story Ashenden tells the ambassador, has an ‘oval face, charming little nose and large blue eyes’, ‘blue starry eyes’.

Alex, the woman gymnast the British ambassador has an affair with, has ‘a great deal of hair, golden, but obviously dyed, and large china-blue eyes’.

On the trans-Siberian Express he meets an American salesman and – yes, you guessed it:

Mr. John Quincy Harrington was a very thin man of somewhat less than middle height, he had a yellow, bony face, with large, pale-blue eyes…

And in Sanatorium, when Ashenden is wheeled out onto the sundeck he finds:

On the other side of Ashenden was lying a pretty girl, with red hair and bright blue eyes; she had on no make-up, but her lips were very red and the colour on her cheeks was high.

A new patient arrives at the sanatorium.

After Ashenden had been for some time at the sanatorium there came a boy of twenty. He was in the navy, a sub-lieutenant in a submarine, and he had what they used to call in novels galloping consumption. He was a tall, good-looking youth, with curly brown hair, blue eyes and a very sweet smile. (p.226)

Blue eyes everywhere.

Style

In my review of short stories volume two I highlighted Maugham’s odd way with the word order in his sentences, and attributed it, maybe, to his Victorian roots i.e. as a hangover from the Victorian prose he was raised on.

But I’ve changed my mind. All the Ashenden stories are set abroad and require the protagonist to speak either French or German and, as the foreign locale and the snippets of German or French quoted in the text began to sink in, it dawned on me that the Victorian thesis may be wrong.

All the biographies mention that Maugham was born and raised in the British Embassy in Paris and that French was his first language. Maybe that’s the origin of his odd word order; maybe he’s thinking in French. And maybe his rather foreign approach to English sentence structure was compounded when he spent some years as a student in Heidelberg learning German.

Sentences like the following occur on every page and are not, I suggest, the phraseology that any native English speaker would use.

Two sailors went to the side of the boat and withdrew a bar to allow passage for the gangway, and looking again Ashenden through the howling darkness saw mistily the lights of the quay.

Though he made the journey so often he had always a faint sense of trepidation…

These men were even stupider than he thought; but Ashenden had always a soft corner in his heart for the stupid… (p.18)

A police officer amiable is more dangerous to the wise than a police officer aggressive. (p.19)

Her surname, so far from Teutonic, she owed to her grandfather. (p.25)

He did not know if it was his fancy that he read in her eyes now the despairing thought that she had not the time to wait. (p.38)

The sun was shining as brightly as usual on the square, the shabby little carriages with their scrawny horses, had the same air as before, but they did not any longer fill Ashenden with gaiety. (p.68)

He did not know what were the Mexican’s plans.

Ashenden was in the habit of asserting that he was never bored. It was one of his notions that only such persons were as had no resources in themselves. (p. 77)

He found the carriage in which Guilia Lazzari was, but she sat in a corner… (p.92)

They walked down the hill and reaching the quay for shelter from the cold stood in the lee of the custom-house. (p.101)

He wondered what had been her origins. (p.104)

Ashenden wondered if Gustav was aware that a typewriter could betray its owner as certainly as a handwriting. (p.117)

Most of the hotels were closed, the streets were empty, the rowing boats for hire rocked gently at the water’s edge and there were none to take them. (p.118)

Then entered a very old tall bent man. (p.120)

That frank, jovial red face bore then a look of shifty cunning. (p.122)

He had naturally a pale face and never looked as robust as he was. (p.128)

The shadow of a breeze fluttered the green leaves of the trees; everything invited to a stroll. (p.129)

Ashenden knew in Lucerne a Swiss who was willing on emergency to do odd jobs. (p.141)

Ashenden waited in the hall for a quarter of an hour so that there should appear in him no sign of hurry…

Presently he received a letter from the consul in Geneva to say that Caypor had there applied for his visa…

She was disappointed, but not yet anxious; she knew how irregular at that time was the post. (p.144)

Except to go morning and afternoon to Cook’s she spent apparently the whole day in her room. (p.145)

When first Ashenden met Byring he did not very much take to him. (p.159)

He did not keep his promise. He made her terrific scenes. (p.175)

It’s English, Jim, but not as we know it.

The only man on the ship who spoke English was the purser and though he promised Ashenden to do anything he could to help him, Ashenden had the impression that he must not too greatly count upon him. (p.179)

After Ashenden had been for some time at the sanatorium there came a boy of twenty.

I have given so many examples to show that this unEnglish influence isn’t an occasional hiccup, it is intrinsic to Maugham’s prose style and plays an important part in creating the strange detached, slightly otherworldly effect which Maugham’s stories have on the reader.

Ashenden

Maugham went on to use Ashenden as the narrator of the later novels Cakes and Ale (1930) and The Razor’s Edge (1944).