|

| Téa Obreht |

The 10 Best Debut Novels

of the Decade

Emily Temple

23 December, 2019

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists, and it’s only appropriate to begin our journey with the best debut novels published in English between 2010 and 2019.

The following books were chosen after much debate (and several rounds of voting) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. Feel free to add any favorites we’ve missed in the comments below.

***

The Top Ten

TÉA OBREHT, THE TIGER’S WIFE

TÉA OBREHT, THE TIGER’S WIFE

(2011)

It’s easy to forget, reading The Tiger’s Wife, that Obreht was only 25 when it was published in 2011 (that year, she became the youngest-ever winner of the UK’s Orange Prize—and did you know it was the first book ever sold by her agent, and the second book ever acquired by her editor? Yes, I feel bad too.). I say “easy to forget,” but it might be more accurate to say “hard to believe,” because this debut is so ambitious, so assured, and so richly textured that it feels like something that could only come from decades of toil.

It is an astonishing book for a writer of any age, half fable, half gritty portrait of an unnamed Balkan country recovering from civil war. It is a novel about story, and about family, two things that inform and describe one another. “Everything necessary to understand my grandfather lies between two stories,” our narrator Natalia tells us, “the story of the tiger’s wife, and the story of the deathless man. These stories run like secret rivers through all the other stories of his life.” Part of the magic of Obreht’s writing (it’s also true in her latest novel, Inland) is how secure you feel in the worlds she creates—the feeling is akin to stepping into a photograph, or a documentary: you look around and clock every detail; you never doubt. You can feel reality hovering underneath the sentences, even when they’re describing something patently impossible. And yet in this novel, she’s always reminding you how these worlds can change, and how we can change them in the telling.

In addition to winning the Orange Prize, the novel was a National Book Award finalist and a New York Times bestseller; it also secured Obreht’s (obviously well-deserved) spot on the New Yorker’s 20 under 40 list. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

JUSTIN TORRES, WE THE ANIMALS

JUSTIN TORRES, WE THE ANIMALS

(2011)

Every time I write about Torres’s exquisite, intense debut, I find I have to quote the opening, which goes like this:

We wanted more. We knocked the butt ends of our forks against the table, tapped our spoons against our empty bowls; we were hungry. We wanted more volume, more riots. We turned up the knob on the TV until our ears ached with the shouts of angry men. We wanted more music on the radio; we wanted beats; we wanted rock. We wanted muscles on our skinny arms. We had bird bones, hollow and light, and we wanted more density, more weight. We were six snatching hands, six stomping feet; we were brothers, boys, three little kings locked in a feud for more.

It goes on like that. This is a slim novel—my copy has only 125 pages—which makes its intensity all the more impressive; not a word or moment wasted. When I say that it is poetic, I mean it in the most literal of ways: it relies on meter, on sound, on anaphora. You feel it as much as you understand it, like a chant. The story moves slowly from the plurality of childhood—the “we” of the opening—to the individuality of young adulthood, in this case, one boy realizing his in unlike his brothers in a fundamental way.

Improbably, the novel was made into a gorgeous film last year, which you should all find a way to see. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

NOVIOLET BULAWAYO, WE NEED NEW NAMES

NOVIOLET BULAWAYO, WE NEED NEW NAMES

(2013)

The kids in NoViolet Bulawayo’s debut are the vibrant hearts of a book that at times reads like a fable. This is partly because of the names the title alludes to, those missing and misaligned and poorly understood. A young girl called Darling and her friends—with nicknames like Bastard and Godknows—wander through the surroundings of a Zimbabwean shantytown that the children call Paradise (“a place we will soon be leaving”). Bulawayo creates one of the indelible contemporary portraits of a child’s friend group, characterized by distillations of playfulness, contempt, solidarity—unadulterated emotions in the young, and yet, for Darling and company, unable to be identified or named in the adult world. This is a world that, Bulawayo suggests, misleads with false assurances: an abortion is best performed with a clothes hanger, only grandfathers can be president, the pastor at church is healing that demon-possessed woman by placing his hands on her and nothing more. The world beyond child’s play produces patronizing NGO workers, stupid tourists, and bulldozers that raze towns. Darling eventually leaves home to live with her aunt in “Destroyed, Michigan” (one of the granular delights of the novel is Bulawayo’s dexterous, often funny wordplay and onomatopoeic flair). Detroit, like Paradise, is a place of myth (“With the cold and dreariness, this place doesn’t look like my America, doesn’t even look real”), and Bulawayo is interested in how we get to places like these and why we leave. Throughout Darling’s acclimation period to life in America, memories of her childhood resurface and relationships with her old friends turn cold. Ultimately we understand that Paradise won’t be regained. We Need New Names brought us Bulawayo’s remarkably assured voice (the same year that another great sub-Saharan Africa-to-America immigrant epic, Americanah, was published). Bulawayo took the temperature, so to speak, on the eve of the Mediterranean migrant crisis, with an intimate story of a young woman always looking for home. –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

VIET THANH NGUYEN, THE SYMPATHIZER

VIET THANH NGUYEN, THE SYMPATHIZER

(2015)

“I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces.” From the very first line of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s brilliant debut, I could tell this book was going to make literary history. When The Sympathizer won both the Pulitzer Prize and the Edgar Award, I was glad to see the world agreed. The Sympathizer’s premise sets up its many complicated acts—a child born to a young Vietnamese mother and a dissolute French Catholic priest must flee to South Vietnam for the sins of his parentage; there, he is recruited as a secret agent to spy on his countrymen, and soon enough, turns double agent by the North to spy on his powerful patrons in the South, his position complicated by his refugee flight to California, where he falls in love with the rebellious daughter of a former general who once employed him.

Oh, sympathizer, how shall I count the ways in which I love thee? The Sympathizer‘s brilliance is manyfold: the perspective of a double agent makes us privy to secrets and allows us entrance to rationalizations on all sides of the Vietnam conflict; the nameless spy’s peregrinations follow an Odyssean route to exile and then home, culminating in a Lord of the Rings-esque return to the shire only to find it controlled by petty dictators; a parody of Apocalypse Now encapsulates everything that is wrong with both Hollywood and the American interpretation of authenticity. There are many reasons to sing the praise of this singular text. While frequently earning comparison to Graham Green and John le Carre, The Sympathizer is also a meditation on identity, exile, culture, history, and so much more. I can’t recommend this book enough. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

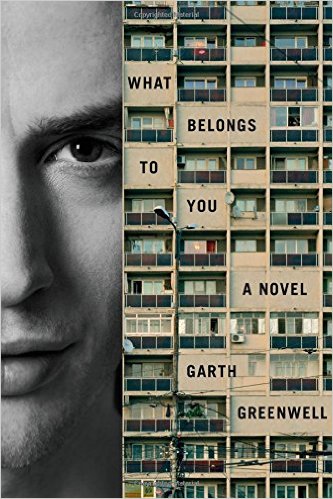

GARTH GREENWELL, WHAT BELONGS TO YOU

GARTH GREENWELL, WHAT BELONGS TO YOU

(2016)

The first section of Garth Greenwell’s debut is almost a love story: a young man teaching English in Sofia, Bulgaria meets a hustler named Mitko while cruising in a public bathroom. But as their relationship unfolds, it becomes not quite a romance, though not not a romance: something stickier and stranger and more real than you typically encounter in novels.