Like tens of thousands of young women before me, I wrote to Judy Blume because something strange was happening to my body.

I had just returned from visiting the author in Key West when I noticed a line of small, bright-red bites running up my right leg. I was certain it was bedbugs—and terrified that I’d given them to Blume, whose couch I had been sitting on a few days earlier.

I figured that if the creatures had hitched a ride from my hotel room, as I suspected, the courteous—if mortifying—thing to do would be to warn Blume that some might have stowed away in her upholstery, too.

In Key West and in Brooklyn, beds were stripped, expensive inspections performed: nothing. After a few days, I had no new bites. I was relieved, if further embarrassed. I apologized to Blume for the false alarm, and she responded with a “Whew!” I hoped we had put the matter behind us.

The next morning, another email appeared in my inbox:

Amy—When I am bitten by No-See-Ums (so small you can’t even see them and you were eating on your balcony in the evening)—I get a reaction, very itchy and the bites get very red and big. They often bite in a line.

It was “just a thought,” she wrote. “xx J.”

Here was Judy Blume, the author who gave us some of American literature’s most memorable first periods, wet dreams, and desperate preteen bargains with God, calmly and empathetically letting me know that an unwelcome bodily development was nothing to be ashamed of or frightened by—that it was, in fact, something that had happened to her body too. Maybe, on some level, I’d been seeking such reassurance when I emailed her in the first place. Who better to go through a bedbug scare with?

For more than 50 years, Blume has been a beloved and trusted guide to children who are baffled or terrified or elated by what is happening to them, and are trying to make sense of it, whether it has to do with friendship, love, sex, envy, sibling rivalry, breast size (too small, too large), religion, race, class, death, or dermatology. Blume’s 29 books have sold more than 90 million copies. The New York Daily News once referred to her as “Miss Lonelyhearts, Mister Rogers and Dr. Ruth rolled into one.” In the 1980s, she received 2,000 letters every month from devoted readers. “I’m not trying to get pity,” a typical 11-year-old wrote. “What I want is someone to tell me, ‘You’ll live through this.’ I thought you could be that person.”

Blume, now 85, says that she is probably done writing, that the novel she published in 2015 was her last big book. She doesn’t get many handwritten letters anymore, though she still interacts with readers in the nonprofit bookstore that she and her husband, George Cooper, founded in Key West in 2016. Some fans, women who grew up reading Blume, cry when they meet her. “Judy, hi!” one middle-aged visitor exclaimed when I was there, as if she were greeting an old friend. She was from Scotch Plains, New Jersey, where Blume raised her two children in the ’60s and ’70s, though she admitted that the author would have no reason to know her personally. “Well hello, and welcome!” Blume said.

Blume loves meeting kids in the store too. Usually, though, she avoids making recommendations in the young-adult section—not because of the kids so much as their hovering parents. “The parents are so judgmental ” about their kids’ book choices, she told me. “They’re always, you know, ‘What is this? Let me see this.’ You want to say, ‘Leave them alone.’ ” (Key West is a tourist town, and not everyone knows they’re walking into Judy Blume’s bookstore.)

Such parental anxiety is all too familiar to Blume. In the ’80s, her frank descriptions of puberty and teenage sexuality made her a favorite target of would-be censors. Her books no longer land on the American Library Association’s Top 10 Most Challenged Books list, which is now crowded with novels featuring queer and trans protagonists. Yet Blume’s titles are still the subjects of attempted bans. Last year, the Brevard County chapter of Moms for Liberty, a right-wing group based in Florida, sought to have Forever … taken off public-school shelves there (the novel tells the story of two high-school seniors who fall in love, have sex, and—spoiler—do not stay together forever). Also in 2022, a Christian group in Fredericksburg, Texas, called Make Schools Safe Again targeted Then Again, Maybe I Won’t (it mentions masturbation).

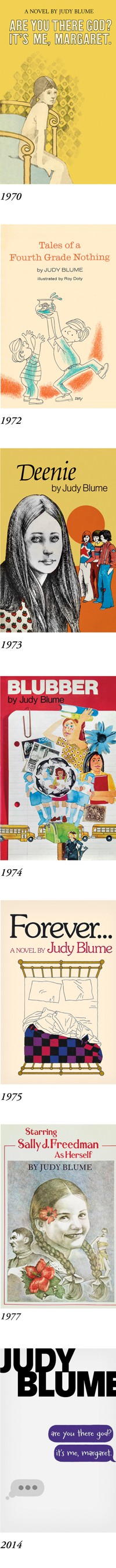

These campaigns are a backhanded compliment of sorts, an acknowledgment of Blume’s continued relevance. Her books remain popular, in part because a generation that grew up reading Blume is now old enough to introduce her to their own children. Some are pressing dog-eared paperbacks into their kids’ hands; others are calling her agent. In April, the director Kelly Fremon Craig’s film adaptation of Blume’s 1970 novel Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret will open in theaters. Jenna Bush Hager is bringing Blume’s novel Summer Sisters to TV. (Hager and her twin, Barbara Pierce Bush, have said that Summer Sisters is the book that taught them about sex.) An animated Superfudge movie is coming to Disney+, and Netflix is developing a series based on Forever … . This winter, the documentary Judy Blume Forever premiered at Sundance Film Festival (it will be streaming on Amazon Prime Video this spring).

Today’s 12-year-olds have the entire internet at their disposal; they hardly need novels to learn about puberty and sex. But kids are still kids, trying to figure out who they are and what they believe in. They’re getting bullied, breaking up, making best friends. They are looking around, as kids always have, for adults who get it.

They—we—still need Judy Blume.

I got my first email from Blume two weeks before my trip. “Hi Amy—It’s Judy in Key West,” she wrote. “Just want to make sure your trip goes well.” I hadn’t planned to consult the subject of my story on the boring logistics of the visit, but those details were exactly what Blume wanted to discuss: what time my flight landed, where I was staying, why I should stay somewhere else instead. Did I need a ride from the airport?

The advice continued once I arrived: where to eat, the importance of staying hydrated, why she prefers bottled water to the Key West tap. (Blume also gently coached me on what to do when, at dinner my first night, my water went down the wrong pipe and I began to choke. “I know what that’s like,” she volunteered. “Bend your chin toward your chest.”) I’d forgotten to bring a hat, so Blume loaned me one for rides in her teal Mini convertible and a walk along the beach. When I hesitated to put it on for the walk, eager to absorb as much vitamin D as possible before a long New York winter, she said, “It’s up to you” in that Jewish-mother way that means Don’t blame me when you get a sunburn and skin cancer. I put on the hat.

Blume and Cooper came here on a whim in the 1990s, during another New York winter, when Blume was trying to finish Summer Sisters. “I would say to George, ‘I wonder how many summers I have left,’ ” Blume recalled. “He said, ‘You know, you could have twice as many if you lived someplace warm.’ ” (Cooper, a former Columbia Law professor, was once an avid sailor.) Eventually they started spending most of the year here.

Blume enjoys a good renovation project, and she and Cooper have lived in various places around the island over the years. They now own a pair of conjoined condos right on the beach, in a 1980s building whose pink shutters and stucco arches didn’t prepare me for the sleek, airy space they’ve created inside, filled with art and books and comfortable places to read while watching the ocean. In the kitchen, a turquoise-and-pink tea towel with a picture of an empty sundae dish says I go all the way.

At one end of the apartment is a large office where Blume and one of her assistants work when she’s not at the bookstore. Her desk faces the water and is littered with handwritten notes and doodles she makes while she’s on the phone. She plays Wordle every day using the same first and second words: TOILE and SAUCY.

Usually, Blume told me, she sleeps with the balcony door open so she can hear the waves, though she’s terrified of thunderstorms, so much so that she used to retreat into a closet when they arrived. This condo has thick hurricane glass that lessens the noise, and now, with a good eye mask, Blume can bear to wait out a storm.

Blume spoke about her anxieties, and her bodily travails, without a hint of embarrassment. When I visited, she was still recovering from a bout of pneumonitis, a side effect of a drug she’d been prescribed to treat persistent urinary-tract infections. It had been months since she’d felt up to riding her bike—a cruiser with bright polka dots painted by a local artist—or been able to walk at quite the pace she once did (though our morning walk was, in my estimation, pretty brisk). Lately, she had been snacking on matzo with butter to try to regain some of the weight she’d lost over the summer.

Blume’s fictional characters are memorably preoccupied with comparing height and bra size and kissing techniques, as Blume herself was in her preteen and teenage years. Nowadays, when she has lunch with her childhood friends Mary and Joanne, with whom she’s stayed close, the three talk about things like hearing aids, which Mary had recently argued should be avoided because they make one seem old. But Joanne said that nothing makes someone seem older than having to ask “What?” all the time, and Blume, a few weeks into using her first pair, was glad she’d listened to Joanne.

Her body is changing, still. “I’m supposed to be five four. I’ve always been five four,” Blume said during breakfast on her balcony. “And recently the new doctor in New York measured me, and I said, ‘It better be five four.’ ” It was 5 foot 3 and a quarter. “I said, ‘No!’ And yet, I have to tell you, all this year I’ve been saying to George, ‘I feel smaller.’ It’s such an odd sensation.”

She knows it happens to everyone, eventually, but she thought she’d had a competitive advantage: tap dancing, which she swears is good for keeping your posture intact and your spine strong. Her favorite teacher no longer works in Key West. But some nights, Cooper will put on Chet Baker’s fast-paced rendition of “Tea for Two,” and she has no choice. “I have to stop and tap dance.”

Before she was Judy Blume, tap-dancing author, she was Judy Sussman, who danced ballet—“That’s what Jewish girls did”—and made up stories that she kept to herself. She grew up in Elizabeth, New Jersey, where her father, Rudolph Sussman, was a dentist, and the kind of person everyone confided in; his patients would come to his office just to talk. Her mother, Esther, didn’t work. Her brother, David, four years her senior, was a loner who was “supposed to be a genius” but struggled in school. Blume distinguished herself by trying hard to please her parents. “I knew that my job was making the family happy, because that wasn’t his job,” she told me.

She felt that her mother, in particular, expected perfection. “I didn’t doubt my parents’ love for me, but I didn’t think they understood me, or had any idea of what I was really like,” she has written. “I just assumed that parents don’t understand their kids, ever. That there is a lot of pretending in family life.”

As a child, Blume read the Oz books and Nancy Drew. The first novels she felt she could identify with were Maud Hart Lovelace’s Betsy-Tacy books. When she was 11, the book she wanted to read most was John O’Hara’s A Rage to Live, but she wasn’t allowed (it has a lot of sex, as well as an awkward mother-daughter conversation about periods). She did read other titles she found on her parents’ shelves: The Catcher in the Rye, The Fountainhead, The Adventures of Augie March.

In the late 1940s, David developed a kidney condition, and to help him recuperate, the Sussmans decided that Esther and her mother would take the children to Miami Beach for the school year (Rudolph stayed behind in New Jersey so he could keep working). Blume’s 1977 novel, Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself, is based on this time in her life. Its protagonist, 10-year-old Sally, is smart, curious, and observant, occasionally in ways that get her into trouble. She asks her mother why the Black family she befriends on the train has to switch cars when they arrive in the South, and is angry when her mother, who admits that it may not be fair, tells her that segregation is simply “the way it is.” She has vivid, sometimes gruesome fantasy sequences about personally confronting Hitler.

When Sally finds out that her aunt back home is pregnant, she writes her a celebratory letter full of euphemisms she only half-understands; her earnest desire to discuss the matter in adult terms even as she professes her ongoing fuzziness on some key details makes for a delicious bit of Blume-ian humor: “Congratulations! I’m very glad to hear that Uncle Jack got the seed planted at last.” What Sally really wants to know is “how you got the baby made.”

Blume, who hit puberty late, had similar questions at that age. She faked menstrual cramps when a friend got her period in sixth grade, and even wore a pad to school for her friend to feel through her clothes, as evidence. When she was 14 and still hadn’t gotten her period, Esther picked her up from school one day and brought her to a gynecologist’s office. Blume later recalled that the doctor barely spoke to her at all. “He put my feet in stirrups, and without warning, he examined me.” She cried all the way home. “Why didn’t you tell me he would do that?” she asked her mother. “I didn’t want to frighten you,” her mother replied. Blume was furious.

Her father, the dentist, was slightly more helpful. When she caught impetigo at school as a teenager, she developed sores on her face and scalp—and “down there,” as she put it. “I asked my father how I was going to tell the doctor that I had it in such a private place,” Blume has written. “My father told me the correct way to say it. The next day I went to the doctor and I told him that I also had it in my pubic hair.” Blume “turned purple” saying the words, but the doctor was unfazed. She learned that there was power in language, in knowing how to speak about one’s body in straightforward, accurate terms.

She went to NYU, where she majored in early-childhood education. She married her first husband, a lawyer named John Blume, while she was still in college. For their honeymoon, Blume packed a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover that her brother had brought home from Europe. It was still banned in the United States. “That book made for a great honeymoon,” she has said.

Blume graduated from college in 1961; that same year, her daughter, Randy, was born, and in 1963 she had a son, Larry. She’d always loved babies, and loved raising her own. But being a Scotch Plains housewife gave her stomach pains—a physical manifestation, she later said, of her discontent.

“I desperately needed creative work,” Blume told me. “That was not something that we were raised to think about in the ’50s, the ’40s. What happens to a creative kid who grows up? Where do you find that outlet?”

Blume spent “God knows how long” making elaborate decorations for dinner parties—for a pink-and-green-themed “evening in Paris,” she created a sparkling scene on the playroom wall complete with the River Seine and a woman selling crepe-paper flowers from a cart. She was never—still isn’t—a confident cook. “I used to have an anxiety dream before dinner parties that I would take something out of the fridge that was made the day before and I’d drop it,” she told me.

“I didn’t fit in with the women on that cul-de-sac,” she said. “I just never did. I gave up trying.” She stopped pretending to care about the golf games and the tennis lessons. She started writing.

The first two short stories Blume sold, for $20 each, were “The Ooh Ooh Aah Aah Bird” and “The Flying Munchkins.” Mostly, she got rejections.

In 1969, she published her first book, an illustrated story that chronicled the middle-child woes of one Freddy Dissel, who finally finds a way to stand out by taking a role as the kangaroo in the school play. She dedicated it to her children—the books she read to them, along with her memories of her own childhood, were what had made her want to write for kids.

Around the same time, Blume read about a new publishing company, Bradbury Press, that was seeking manuscripts for realistic children’s books. Bradbury’s founders, Dick Jackson and Robert Verrone, were young fathers interested, as Jackson later put it, in “doing a little mischief” in the world of children’s publishing. Blume sent in a draft of Iggie’s House, a chapter book about what happens when a Black family, the Garbers, moves into 11-year-old Winnie’s all-white neighborhood. Bradbury Press published the book, which is told from Winnie’s perspective, in 1970.

Today, Blume cringes when she talks about Iggie’s House—she has written that in the late 1960s, she was “almost as naive” as Winnie, “wanting to make the world a better place, but not knowing how.” In many ways, though, the novel holds up; intentionally or not, it captures the righteous indignation, the defensiveness, and ultimately the ignorance of the white “do-gooder.” (“I don’t think you understand,” Glenn, one of the Garber children, tells Winnie. “Understand?” Winnie asks herself. “What did he think anyway? Hadn’t she been understanding right from the start. Wasn’t she the one who wanted to be a good neighbor!”)

The major themes of Blume’s work are all present in Iggie’s House : parents who believe they can protect their kids from everything bad in the world by not talking to them about it, and kids who know better; families attempting to reconcile their personal value systems with shifting cultural norms. Years later, Blume asked Jackson what he’d seen in the book. “I saw the next book, and the book after that,” he said.

After Iggie’s House, Blume published the novel that would, more than any other, define her career (and earn Bradbury its first profits): Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

Margaret Simon is 11 going on 12, newly of suburban New Jersey by way of the Upper West Side. She’s worried about finding friends and fitting in, titillated and terrified by the prospect of growing up (the last thing she wants is “to feel like some kind of underdeveloped little kid,” but “if you ask me, being a teenager is pretty rotten”). When Margaret came out, the principal of Blume’s kids’ school didn’t want it in the library; he thought elementary-school girls were too young to read about periods.

I remembered Margaret as a book about puberty, and Margaret’s chats with God as being primarily on this subject. Some of them, of course, are. (“Please help me grow God. You know where. I want to be like everyone else.”) But reading the book again, I was reminded that it is also a thoughtful, at times profound meditation on what it means to define your own relationship to religious faith.

Margaret’s Christian mother and Jewish father are both proudly secular. She fears that if they found out about her private prayers, “they’d think I was some kind of religious fanatic or something.” Much to their chagrin, she attends synagogue with her grandmother and church with her friends. She’s trying to understand what her parents are so opposed to, and what, if anything, these institutions and rituals might have to offer.

Several Blume fans I talked with remembered this aspect of the novel far better than I did. The novelist Tayari Jones, whose career Blume has championed, told me that the way Margaret is torn between “her parents’ decisions and her grandparents’ culture” was the main reason she loved the book. “I’m Black, and I grew up in the South. Being raised without religion made me feel like such an oddball,” Jones told me. “That really spoke to me even more than the whole flat-chested thing, although there was no chest flatter than my own.”

The writer Gary Shteyngart first encountered Margaret as a student at a Conservative Jewish day school. He found the questions it raised about faith “mind-blowing.” “I think in some ways it really created my stance of being apart from organized religion,” he told me. (The book stuck with him long after grade school; Shteyngart recalled repeating its famous chant—“I must, I must, I must increase my bust!”—with a group of female friends at a rave in New York in the ’90s. “I think we were on some drug, obviously.”)

Margaret was not a young-adult book, because there was no such thing in 1970. But even today, Blume rejects the category, which is generally defined as being for 12-to-18-year-olds. “I was not writing YA,” she told me. “I was not writing for teenagers.” She was writing, as she saw it, for “kids on the cusp.”

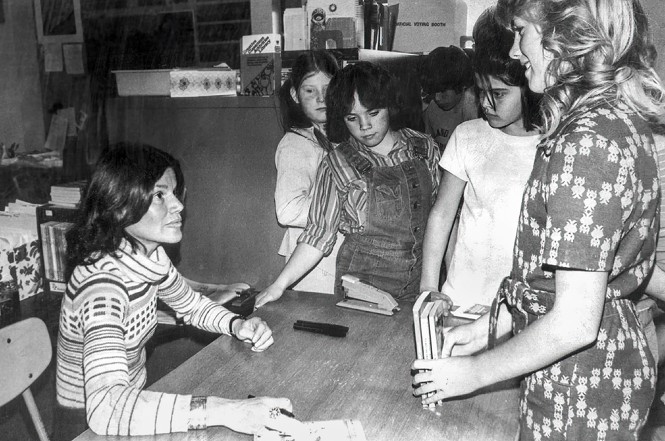

The letters started right after Margaret. The kids wrote in their best handwriting, in blue ink or pencil, on stationery adorned with cartoon characters or paper torn out of a notebook. They sent their letters care of Blume’s publisher. “Dear Judy,” most began. Girls of a certain age would share whether they’d gotten their period yet. Some kids praised her work while others dove right in, sharing their problems and asking for advice: divorce, drugs, sexuality, bullying, incest, abuse, cancer. They wanted to scream. They wanted to die. They knew Judy would understand.

Blume responded to as many letters as she could, but she was also busy writing more books—she published another 10, after Margaret, in the ’ 70s alone. It’s Not the End of the World (1972) took on the subject of divorce from a child’s perspective with what was then unusual candor. “There are some things that are very hard for children to understand,” an aunt tells 12-year-old Karen. “That’s what people say when they can’t explain something to you,” Karen thinks. “I can understand anything they can understand.”

Blume’s mother, Esther, was her typist up until Blume wrote Forever …, her 1975 novel of teen romance—and sex. The book is dedicated to Randy, then 14, who had asked her mother to write a story “about two nice kids who have sex without either of them having to die.” Forever … got passed around at sleepovers and gained a cult following; it is a book that women in their 50s can still recite the raciest page numbers from (85 comes up a lot). It’s also practical and straightforward: how to know if you’re ready, how to do it safely. The protagonist’s grandmother, a lawyer in Manhattan, bears more than a passing resemblance to her creator, mailing her granddaughter pamphlets from Planned Parenthood and offering to talk whenever she wants. “I don’t judge, I just advise,” she says.

The same year Forever … came out, Blume got divorced after 16 years of marriage, and commenced what she has referred to as a belated “adolescent rebellion.” She cried a lot; she ate pizza and cheesecake (neither of which she’d had much interest in before, despite living in New Jersey). Within a year, she had remarried. She and her children and her new physicist husband—Blume calls him her “interim husband”—landed in Los Alamos, New Mexico, where he had a job. Blume knew from the start that the marriage was a mistake, though she didn’t want to admit it. “He was very much a know-it-all,” she told me. “It just got to be too much.” She was unhappy in Los Alamos, which felt like Stepford, but she kept writing. By 1979, she was divorced again.

In the midst of this second adolescence, Blume published her first novel for adults. Wifey, about the sexual fantasies and exploits of an unhappy New Jersey housewife, came out in 1978. She never intended to stop writing for children, though some assumed that Wifey’s explicitness would close that door. After the novel was published, Blume’s mother ran into an acquaintance from high school on the street. Bess Roth, whose son was Philip Roth, had some advice for her. “When they ask how she knows those things,” she told Esther, “you say, ‘I don’t know, but not from me!’ ”

In December 1979, George Cooper, who was then teaching at Columbia, asked his ex-wife if she knew any women he might want to have dinner with while he was visiting New Mexico, where she lived with their 12-year-old daughter. Cooper showed his daughter the four names on the list. His daughter, being 12, told him he had to have dinner with Judy Blume.

Dinner was Sunday night; Monday, Blume and Cooper saw Apocalypse Now. He called and sang “Love Is the Drug” over the phone (Blume thought he was singing “Love is a bug”). Tuesday night, Blume had a date with someone else. Cooper came over afterward, and he never left. They got married in 1987, to celebrate their 50th birthdays.

“The enjoyment of sexuality should go for your whole life—if you want it to,” Blume told the writer Jami Attenberg, in a 2022 conversation at the Key West Literary Seminar. “If you don’t, fine.” I don’t judge, I just advise. She had a product endorsement to share with the audience: George had given her a sex toy, the Womanizer, and it was fabulous. “Isn’t that wonderful? Isn’t that great? He got it for me and then I sang its praises to all of my girlfriends.”

Blume’s steadfast nonjudgmentalism, a feature of all her fiction, is part of what has so irritated her critics. It’s not just sex that Blume’s young characters get away with—they use bad words, they ostracize weirdos, they disrespect their teachers. In Deenie and Blubber, two middle-grade novels from the ’70s, Blume depicts the cruelty that kids can show one another, particularly when it comes to bodily differences (physical disability, fatness). “I’d rather get it out in the open than pretend it isn’t there,” Blume said at the time. She didn’t think adults could change kids’ behavior; her goal was merely to make kids aware of the effect that behavior could have on others.

In 1980, parents pushed to have Blubber removed from the shelves of elementary-school libraries in Montgomery County, Maryland. “What’s really shocking,” one Bethesda mother told The Washington Post, “is that there is no moral tone to the book. There’s no adult or another child who says, ‘This is wrong.’ ” (Her 7-year-old daughter told the paper that Blubber was “the best book I ever read.”)

[Read: How banning books marginalizes children]

As Blume’s books began to be challenged around the country, she started speaking and writing against censorship. In November 1984, the Peoria, Illinois, school board banned Blubber, Deenie, and Then Again, Maybe I Won’t, and Blume appeared on an episode of CNN’s Crossfire, sitting between its hosts. “On the left, Tom Braden,” the announcer said. “On the right, Pat Buchanan.” Braden tried, sort of, to defend Blume’s work, but Blume was more or less on her own as Buchanan yelled at her: “Can you not understand how parents who have 9-year-olds … would say, ‘Why aren’t the kids learning about history? Why aren’t they learning about the Civil War? What are they focusing in on this nonsense for?’ ” Blume explained that it wasn’t either/or—that her books were elective, that kids read them “for feelings. And they write me over 2,000 letters a month and they say, ‘You know how I feel.’ ”

“ ‘I touched my special place every night,’ ” Buchanan replied, reading from a passage in Deenie about masturbation. (After the bans received national publicity, the Peoria board reversed its decision but said younger students would need parental permission to read the books.)

Despite, or perhaps because of, the censorship, Blume was, in the early ’80s, at the peak of her commercial success. In 1981, she sold more than 1 million copies of Superfudge, the latest book in a series about the charming troublemaker Farley Drexel Hatcher—a.k.a. Fudge—and his long-suffering older brother, Peter. Starting that year, devoted readers could purchase the Judy Blume Diary—“the place to put your own feelings”—though Blume reportedly declined offers to do Judy Blume bras, jeans, and T‑shirts. Mary Burns, a professor of children’s literature at Framingham State College, in Massachusetts, thought Judy Blume was a passing fad, “a cult,” like General Hospital for kids. “You can’t equate popularity with quality,” Burns told The Christian Science Monitor. “The question that needs to be asked is: will Judy Blume’s books be as popular 20 years from now?” Burns, obviously, thought not.

But 20 years later is about when I encountered the books, when my first-grade teacher pressed a vintage copy of Tales of a Fourth Grade Nothing into my hands in the school library one day. I continued reading Blume over the coming years—as a city kid, I was especially intrigued by the exotic life (yet familiar feelings) of the suburban trio of friends in Just as Long as We’re Together (1987) and Here’s to You, Rachel Robinson (1993). In fourth grade, I tried to take Margaret out of my school library and was told I was too young.

I recently went back to that school to speak with the librarian, who is still there. The young-adult category has exploded in the years since I was a student, and these days, she told me, tweens and young teens seeking realistic fiction are more likely to ask for John Green (The Fault in Our Stars), Angie Thomas (The Hate U Give), or Jason Reynolds (Long Way Down) than Judy Blume. She implied that the subjects these authors take on—childhood cancer, police violence, gun violence—make the adolescent angst of Blume’s books feel somewhat less urgent by comparison.

Yet Blume’s books remain popular. According to data from NPD BookScan, Margaret tends to sell 25,000 to 50,000 copies a year; the Fudge series sells well over 100,000. (The Fault in Our Stars, which was published in 2012 and became a movie in 2014, sold 3.5 million copies that year, but has not exceeded 100,000 in a single year since 2015.) A portion of these sales surely comes from parents who buy the books in the hope that their kids will love them as much as they did. But nostalgia alone seems insufficient to account for Blume’s wide readership; parents can only influence their kids’ taste so much. “John Updike once said that the relationship of a good children’s-book author to his or her audience is conspiratorial in nature,” Leonard S. Marcus, who has written a comprehensive history of American children’s literature, told me. “There’s a sense of a shared secret between the author and the child.” Clearly, something about these stories still feels authentic to the TikTok generation.

Now that Blume’s books seem relatively quaint, I asked my former librarian, can anyone who wants to check them out? Absolutely not, she said. Her philosophy is that “the protagonist, especially with realistic fiction, should be around your age range.” It’s not censorship, she insisted, just “asking you to wait.”

Back in 2002 or 2003, not wanting to wait, I’d bought my own copy of Margaret. I loved that book, all the more so because I knew it was one adults didn’t want me to read.

For her part, Blume believes that kids are their own best censors. In Key West, she told me the story of a mother who had reluctantly let her 10-year-old read Forever … on the condition that she come to her with any questions afterward. Her daughter had just one: What is fondue?

“Is growing up a dirty subject?” Blume asked Pat Buchanan on Crossfire. What were adults so afraid of? What made it so hard for them to acknowledge that children were people too? In her fiction, Blume had always taken the kids’ side. But as her own kids got older and she began to reflect on her experience raising them, Blume gained more empathy for parents. In 1986, she published Letters to Judy: What Your Kids Wish They Could Tell You, “a book for every family to share,” featuring excerpts and composites of real letters that children (and a few parents) had sent her over the years, plus autobiographical anecdotes by Blume herself. “If you’re wondering why your child would write to me instead of coming to you,” she wrote, “let me assure you that you’re not alone. There were times when my daughter, Randy, and son, Larry, didn’t come to me either. And that hurt. Like every parent, I’ve made a million mistakes raising my kids.”

When she would describe the project to friends and colleagues, they’d nod and say, “Oh, letters from deeply troubled kids.” Blume corrected them. “I would try to explain,” she wrote, “that yes, some of the letters are from troubled kids, but most are from kids who love their parents and get along in school, although they still sometimes feel alone, afraid and misunderstood.” She admitted in the book’s introduction that “sometimes I become more emotionally involved in their lives than I should.” Blume replied directly to 100 or so kids every month, and the rest got a form letter—some with handwritten notes at the top or bottom. After Letters to Judy came out, more and more kids wrote.

Today, the letters are in the archives of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale. Reading through them is by turns heartwarming, hilarious, and devastating. Some letter-writers ask for dating advice; others detail the means by which they are planning to kill themselves. Blume remembers one girl who said she had the razor blades ready to go.

Blume’s involvement, in some cases, was more than just emotional: She called a student’s guidance counselor and took notes on a yellow Post-it about how to follow up. One teenage girl came to New York, where Blume and Cooper had moved from New Mexico, for a weekend visit (they took her to see A Chorus Line ; she wasn’t impressed). Blume thought seriously about inviting one of her correspondents to come live with her. “It took over my life at one point,” Blume said of the letters, and the responsibility she felt to try to help their writers.

“Hang in there!” Blume would write, a phrase that might have seemed glib coming from any other adult, though the kids didn’t seem to take it that way when she said it: They’d write back to thank her for her encouragement and send her updates.

Her correspondence with some kids lasted years. “I want to protect you from anything bad or painful,” Blume wrote to one. “I know I can’t but that’s how I feel. Please write soon and let me know how it’s going.”

After spending a day in the Beinecke’s reading room, I began to see Blume as a latter-day catcher in the rye, attempting to rescue one kid after the next before it was too late. “I keep picturing all these little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all,” Holden Caulfield tells his younger sister in J. D. Salinger’s novel:

Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around—nobody big, I mean—except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff—I mean if they’re running and they don’t look where they’re going I have to come out from somewhere and catch them.

Perhaps, through these letters, Blume had managed to live out Caulfield’s impossible fantasy.

When your books sell millions of copies, Hollywood inevitably comes calling. Blume, long a skeptic of film or TV collaboration, was always clear with her agent that Margaret was off the table. “I didn’t want to ruin it,” she told me. Some books, she thought, just aren’t meant to be movies. “It would have been wrong somehow.”

Then she heard from Kelly Fremon Craig, who had directed the 2016 coming-of-age movie The Edge of Seventeen. Blume had admired the film, which could have drawn its premise from a lost Judy Blume novel. Its protagonist, Nadine, is an angsty teen who has recently lost her father and feels like her mom doesn’t get her. Fremon Craig and her mentor and producing partner, James L. Brooks, flew to Key West and went to Blume’s condo for lunch. (Blume had it catered—no reason to have anxiety dreams about serving food on a day like that.) They convinced Blume that Margaret could work on the screen.

Blume served as a producer on the film, gave Fremon Craig notes on the script, and spent time on set, heading off at least one catastrophic mistake when she observed the young actors performing the famous “I must increase my bust” exercise by pressing their hands together in a prayer position. (The correct method, which Blume has demonstrated—with the caveat that it does not work—is to make your hands into fists, bend your arms at your sides, and vigorously thrust your elbows back.)

The result of their close collaboration is an adaptation that’s generally faithful to the text. Abby Ryder Fortson, who plays Margaret, manages to make her conversations with God feel like a natural extension of her inner life.

If anything, the movie is more conspicuously set in 1970 than the book itself, full of wood paneling, Cat Stevens, and vintage sanitary pads. Blume told me that Margaret is really about her own experience growing up in the ’50s; she just happened to publish it in 1970. The movie, unfolding at what we now know was the dawn of the women’s-liberation movement, adds another autobiographical layer by fleshing out the character of Margaret’s mother, Barbara (Rachel McAdams), who now recalls Blume in her New Jersey–mom era. In the book, Barbara is an artist, and we occasionally hear about her paintings; on-screen, she gives up her career to be a full-time PTA mom. She’s miserable.

Preteens aren’t the only ones in this movie figuring out who they are, and what kind of person they want to become. By the end of the film, Barbara has quit the PTA. She’s happily back at her easel.

I shouldn’t have been surprised by how easy it was to confide in Blume. Still, I hadn’t expected to reveal quite so much—I was there to interview her. Yet over the course of our conversations, I found myself telling her things about my life and my family that I’ve rarely discussed with even my closest friends. At one point, when I mentioned offhand that I’d been an anxious child, Blume asked matter-of-factly, “What were you anxious about when you were a kid?” She wanted specifics. She listened as I ran down the list, asking questions and making reassuring comments. “That’s all very real and understandable,” she said, and the 9-year-old in me melted.

[Read: Judy Blume still has lots to teach us]

It was easy to see why so many kids kept sending letters all those years. Even those of us who didn’t correspond with Blume could sense her compassion. To read one of her books is to have her tell you, in so many words, That’s all very real and understandable.

This kind of validation can be hard to come by. Tiffany Justice, a founder of Moms for Liberty, has said that the group is focused on “safeguarding children and childhood innocence,” an extreme response to a common assumption: that children are fragile and in need of protection, that they are easily influenced and incapable of forming their own judgments. Certain topics, therefore, are best avoided. Even adults who support kids’ learning about these topics in theory sometimes find them too awkward to discuss in practice.

Blume believes, by contrast, that grown-ups who underestimate children’s intelligence and ability to comprehend do so at their own risk—that “childhood innocence” is little more than a pleasing story adults tell themselves, and that loss of innocence doesn’t have to be tragic. In the real world, kids and teenagers throw up and jerk off and fall in love; they have fantasies and fights, and they don’t always buy what their parents have taught them about God.

Sitting across from her in the shade of her balcony, I realized that the impression I’d formed of Blume at the Beinecke Library had been wrong. Much as she had wanted to help the thousands of kids who wrote to her, kids who badly needed her wisdom and her care, Blume was not Holden Caulfield. Instead of a cliff for kids to fall off, she saw a field that stretched continuously from childhood to adulthood, and a worrying yet wonderful lifetime of stumbling through it, no matter one’s age. Young people don’t need a catcher; they need a compassionate coach to cheer them on. “Of course I remember you,” she told the kids in her letters. “I’ll keep thinking of you.” “Do be careful.”

This article appears in the April 2023 print edition with the headline “Judy Blume Goes All the Way.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.